This is part III in a multi-part series estimating how much money Disney made off “Star Wars” in 2019. Go here for my larger series on Disney purchasing Lucasfilm in 2012.)

– Introduction and Feature Films

– Television

– Toys

As a tremendous Star Wars fan, I couldn’t shake the feeling that Star Wars had a rough year. “Rough” from a certain point of view. Consider…

– It arguably had the third most popular TV series in America.

– It definitely had the third most popular film in America.

– And it launched a new “land” in two of it’s parks.

And yet…since this is Star Wars we’re talking about…we’re worried.

The theme parks were the biggest disturbance in the force. Based on hyper-charged expectations, observers expected the new park to be utterly jam packed. Instead, Disney saw a decline in total attendance at Disneyland. Stories about Disneyland being “empty”—for July—were blamed on Star Wars.

On the other hand, Disney raised prices again, finally topping a $200 per day ticket.

It’s all worth unpacking in our continuing series “How Much Money Did Lucasfilm Make in 2019?” (I promise we’ll have this done before the year ends.) This is an extension of the big series I wrote analyzing how much money Star Wars has made for Disney compared to its purchase price. Today it’s all about theme parks, the trickiest business unit to assign value to individual franchises.

(And also the one most impacted by Coronavirus. Unlike past articles, some of which were written pre-Covid-19, I’ll address that in the final section. As a reminder, this series is about 2019, but it does have some forward looking elements.)

Bottom Line, Up Front

In 2019 Star Wars lost about $60 million in total across the theme parks business. The parks still had big costs in 2019 to finish the lands, which hurt the cash flow.

The story is actually more positive than the headlines suggest, though. Disney was able to drive through incredible ticket price increases (the combined average growth rate is well above 6%, depending on the time period). Given that attendance stayed flat in Disneyland and had the second year over year increase at Hollywood Studios, the new lands are working. (At least, until Covid-19 crushes the top and bottom lines.)

Theme Parks – A Cause for Concern?

The performance of Galaxy’s Edge epitomizes Star Wars’s 2019. The “best of times or worst of times” for Victorian literature, or the “light side and dark side” for Star Wars fans.

As befits everything Disney launches, the buzz was phenomenal back in May when it launched. With headlines like this…

That’s Frank Palotta raving about it in CNN. Other outlets and Twitter matched this hype. These positive reviews—generated from previews given to journalists when the lands were virtually empty—matched the reviews of fans. The folks I know who have visited rave about it. I myself haven’t visited because I was worried the lines were too long. And it’s so damn expensive.

Actually, those two latter points really matter. I wasn’t the only one thinking that way. By July, the word was out that Disneyland wasn’t exactly full. It turns out the price increase was doing its job and keeping folks out of the park. Which led to an article in Bloomberg with this headline:

Did Galaxy’s Edge fail then? Not really. If folks were avoiding Disneyland, they weren’t avoiding Galaxy’s Edge, which required reservations to get into for most of the summer and was packed with people. Anecdotally, I think a lot of folks skipped visiting Galaxy’s Edge last year to wait for the crowds to thin out, or for the second ride which debuted in January of this year.

That said, this website is about “business strategy” not a travelogue. From that perspective, two things really matter when evaluating the launch of Galaxy’s Edge. First, Disneyland is thinking very long term with these investments. Like 20 years long time. So if we were evaluating the success of Galaxy’s Edge in July, that’s roughly 1.5% of the time period Disney expect to make it’s money back!

Further, the larger Disney strategy with parks is not to add more people, but to space them out throughout the year while charging them more. That’s summarized by this quote from the Orange County Register.

The goal isn’t to have a one time bump in revenue, but to establish a brand new reason for families to visit every year. Meanwhile, they are charging those fans more to attend, and selling them more things. When Bob Iger says the Star Wars expansions are exceeding expectations—as he did in the first quarter earnings report in January—normally I’d throw my BS flag. In this case, I think the numbers back him up.

But how do we quantify that?

A Reminder – Theme Parks are Devilishly Tough to Assign Value

The last time I modeled theme park revenue, I complained bitterly about how hard it was. With a film, if you know box office, you can pretty well guess at everything else.

Theme parks are more like evaluating a streaming video library. How much value do you assign to an individual TV series at retaining customers? If a streamer watches a dozen shows and four movies in a month, that’s a tough question to answer. (And I’ve attempted this before.)

Likewise, how much credit does any single ride get to bringing someone to Disneyland? Don’t many families go every year? Or multiple times? Or on scheduled vacations? It’s not like Star Wars on its own will bring in families.

Yet, if you didn’t add any new rides, the park would get stagnant. Thus, Disneyland needs to constantly add new attractions, and balance those costs against the expected gains. These new attractions then provide fodder for marketing people, new content for fans who go often and generally keep the park up-to-date.

Further, this is a tougher analysis to make for Disneyland than some other theme parks. For example, the Harry Potter lands at Universal Orlando and Hollywood boosted attendance by up to 30% in some cases. That connection is much tighter than Disneyland, which operates at near capacity anyways.

I model those gains in two ways. First, the increase in attendance year-over-year. Second, the increase in ticket prices (which have outpaced the gains in attendance). Once we have those for theme parks at large, the tough part is just assigning value. Which I’ve done, but it’s the biggest “magic number” in this model.

(What’s a magic number? I explained that in this article, but it’s usually the key number that makes a model work but is also the hardest to model.)

The Theme Park Results – An Analysis

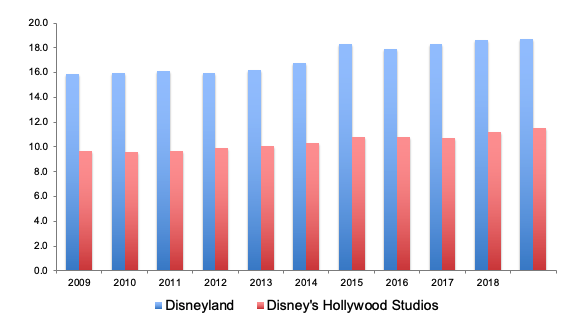

To evaluate 2019, then, we just need to look at visitors and price increases. The story with visitors is fine for Disneyland and great for Hollywood Studios. (For those who don’t know, the Star Wars land in Walt Disney World opened in Disney’s Hollywood Studio, the most poorly attended of the Orlando parks.)

For those expecting blockbuster attendance at Disneyland, the results were mostly flat. However, the people were more spread out throughout the year, which helped Disney improve customer opinion. (Indeed, by December Disney had a day where they had to stop selling tickets.)

(By the way, all these numbers come from the Themed Entertainment Association annual report on theme parks. This report just came out on July 20th, so this data is fresh.)

The story is much better for Hollywood Studios. A park that often lacked a purpose, a Toy Story land opened in 2018 and Galaxy’s Edge opened in 2019. Combined, these new lands have boosted attendance from 10.7 million per year in 2017 to 11.5 million in 2019. (And likely would have gone up again in 2020 had Covid-19 not hit.)

As I said above, the real money make isn’t increasing the number of visitors, but increasing the price per ticket. In that lens, 2019 was another great year for Disney. Ticket prices hit new highs. The quick highlights:

– The top ticket price in 2020 at Disneyland was $154, up from $43 in 2000.

– Disneyland was able to introduce a tiered pricing system, allowing Disneyland to spread out customers throughout the year.

– In just the last 10 years, the average growth rate has been 10.3% at Disneyland, and CAGR of 7.5%.

Indeed, the tiered pricing system worked so well, Disney went from three tiers in 2018 to five tiers in February of this year. Meanwhile, the Hollywood Studios prices have started to match the Magic Kingdom prices.

There is one other piece I’ve modeled which is how much guests spend at the parks. Based on reports and some general industry rule of thumbs, I’ve estimated this at $40 per ticket. However, Iger has said that Galaxy’s Edge have driven this up another 10%, so I increased that in my model.

The Theme Parks Model

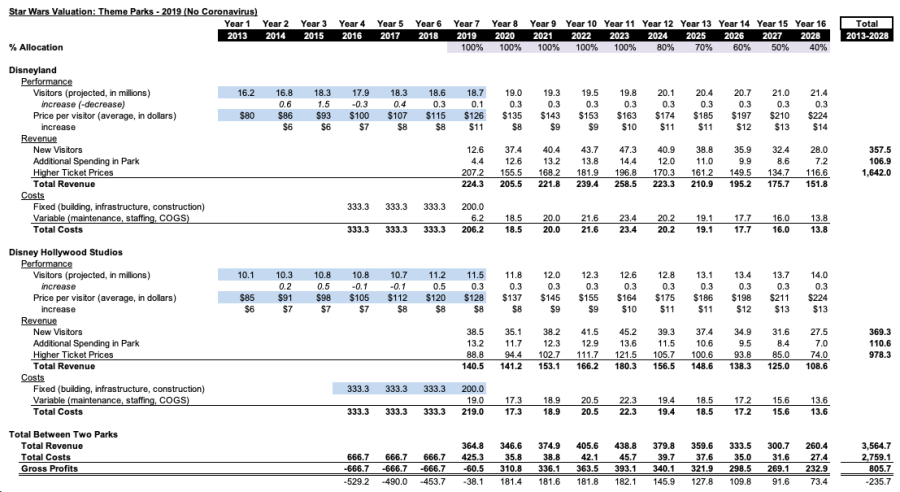

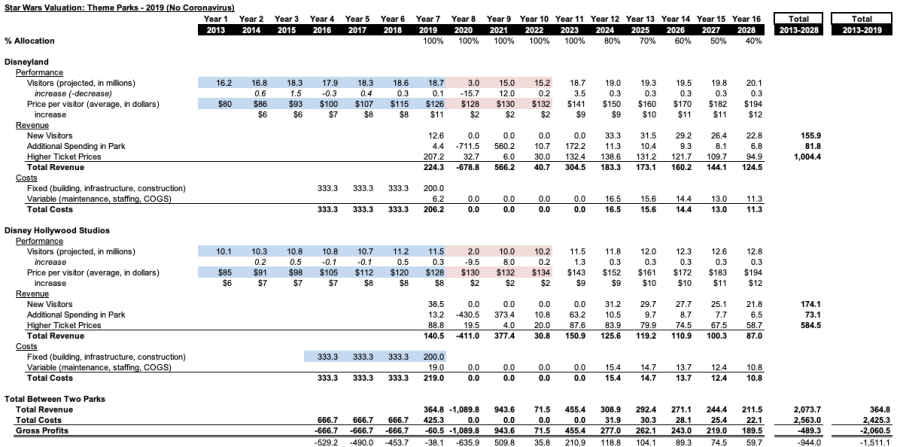

Let’s take that performance and put it into the model. I updated the 2018 and 2019 numbers with the actual performance for visitors, ticket prices and consumer spending. Here’s the results:

My initial estimates for attendance were relatively close. I had guessed that Star Wars could start bumping attendance by 2% at Hollywood Studios, and that’s what happened. (While Disneyland stayed flat, which I did not anticipate.) As a result, my model increased by about $50 million over the course of 2012-2028.

Given the demand for Galaxy’s Edge, I’m still going to allocate value as I had previously, which was starting at 100% of any gains and lowering year over year. These are definitely my magic numbers, and they’re in purple at the top of the model.

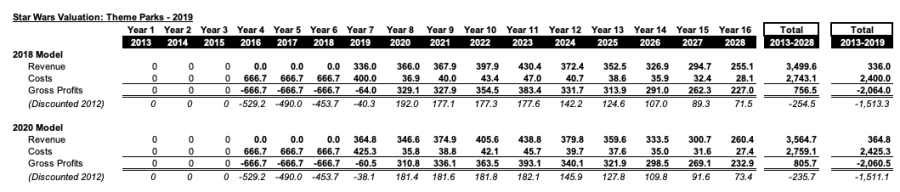

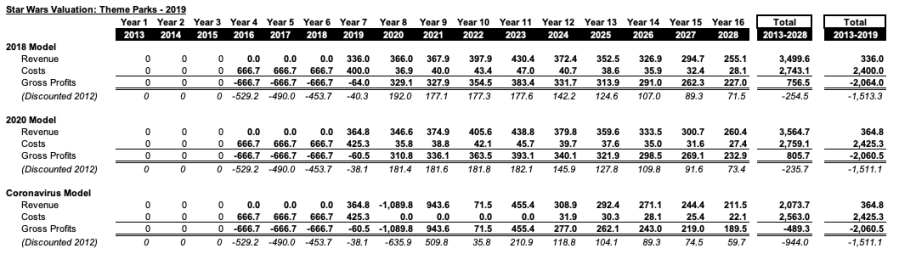

The big worry comes from looking at how much Disney still needs to make on the two Star Wars lands. My model only goes to 2028, and even then I don’t think Disney will make its money back on these two parks. Here’s a comparison:

Of course, we’re not on track for that type of year in 2020, are we?

Coronavirus and Theme Parks

This year is devastating for theme parks. With Disney owning the most valuable theme parks in the world, this is particularly devastating for them.

This doesn’t, though, invalidate the building of Galaxy’s Edge lands. A global pandemic is like a recession: we all knew it was coming, but had no idea when it would happen. When Disney bought Lucasfilm in 2012, it made the right strategic decision to build these two new lands. And again they will pay off for the next two to three decades.

What’s that? You still want to see a coronavirus-impacted model? Fine.

Here’s the comparison to the other two models (my model from 2018, from this year without coronavirus, and with coronavirus).

In other words, a world with coronavirus could cost Disney nearly a $750 million dollars in value. And that’s just the Star Wars allocation. The actual costs are much much higher.

Theme Parks and Resorts: A summary

Money from 2019 (most accurately, operating profit)

It’s a pinch misleading, but likely Star Wars still didn’t make any theme park money this year as it spent big to launch both new parks. It almost broke even, as I allocated most of the price increases in 2019 to Star Wars Galaxy’s Edge. As such, I have Disney losing about $60 million dollars on Star Wars theme parks in 2019.

Long term impacts on the financial model and the 2014 deal

That said, the overall year was positive for the model since the price increases and attendance increases will likely help drive even better profitability in the future. In particular, the spending increase per customer really helps the model long term.

At least, until coronavirus ruined everything.

I think Covid-19 in the average case will still cost Disney about $750 million dollars when it comes to Star Wars. Mainly this comes from the time it will take to get attendance back to pre-coronavirus levels. Though my margin for error is huge with this forecast.

Brand Value

Longer term, I don’t think Galaxy’s Edge will hurt Star Wars brand at all. If anything it will reinforce the brand position. Despite the lack of crowds, the reviews have been phenomenal for Galaxy’s Edge. That’s the piece I can’t look past. Even as the films disappoint (some) folks, the fans still want to relive and experience Star Wars in the real world. By all accounts the park delivers on that.