Last week, we figured out that Mulan was likely watched by 1.2 million Americans on its opening weekend. (Plus or minus 1-1.5 million.) We estimated this means it likely ends up with a global PVOD of $150 million.

But what I didn’t do was explain what all that data means.

Which is today’s article. As I was writing up my implications, I realized I was really writing another entry in my series on the changing film distribution landscape, “Should you release your film straight-to-streaming (Netflix)?” So here’s the latest version of that. As before (See Part I here or Part II here), I’ll be asking myself the questions.

Was the Mulan PVOD “experiment” worth it?

I’m probably too much of a stickler on language–I called out a much more influential strategic technology analyst on Twitter for mixing up aggregation and bundling this week–but I do believe terms of art have a role in setting strategy. Words have meaning and mixing them up can make for sloppy understanding.

The word “experiment” should be reserved for true experiments. Meaning scientifically rigorous processes to draw statistically significant conclusions. In business, this is incredibly hard to do. Most often, we have a sample size of “1”. Given that a company can’t split the universe into multiple alternate realities to see what happens, if they change their strategy they have only one data point to draw conclusions from. They only have the one strategy to adjust. It’s an “n of 1” as I wrote last Wednesday. Meaning we can’t draw conclusions from it.

I prefer “test” instead.

Fine, was the Mulan “test” worth it?

Probably not. Because most “tests” really don’t help refine strategy. Strategically, it’s usually a mistake to run “tests” that muddy your strategy and/or consumer value/brand proposition. In this case, Mulan was huge news. With tens of millions of dollars on the line, you shouldn’t run “tests”, but make strategic decisions that align with your long term strategy.

As it is, Disney got the data that PVOD sales didn’t match their expectations. Consider a question I’ll ask later: What if Disney had released Hamilton on PVOD? Then arguably the test would have worked! But the true difference is one film was the most popular musical of the last decade, and the other was a live-action adaptation. The track record on live-action remakes is more mixed: they’ve had a much more up and down reception. (The Lion King and Beauty and the Beast did really well; Cinderella less so.) In other words, we could have guessed that Mulan could not launch well but Hamilton would have.

But that’s why Disney needs to decide if PVOD is a part of their strategy or not going forward.

Okay, my last try: “Was the Mulan PVOD release strategy the best one to maximize revenue?”

That is the best way to ask the question! Thanks, me.

I think it wasn’t. With the caveat that I’m second guessing the executives, let’s review the options Disney had in front of them. They could release in theaters now, or next year. They could try the PVOD test. They could release in TVOD. Or go straight to SVOD on Disney+.

Trying to run the numbers wouldn’t really help since it would require tons of estimates and just guess work. But if we’re ranking the options, my gut is Disney ended up choosing the 3rd or 4th worst option. I’d do it this way:

1. Release on TVOD in September in Disney+ territories, theaters elsewhere.

2. Release in September in theaters globally, with a shortened window.

3. Release sometime next year in theaters globally.

4. Release on PVOD in September as above.

5. Release straight to SVOD in Disney+ territories, theaters elsewhere.

Here’s my logic for number one: Mulan had higher brand equity than Trolls: World Tour, so it would have generated more interest. Indeed, the biggest release tactic that held Mulan back wasn’t the price, it was the distribution strategy. However, you could convince me that options 2 and 3 could have beat option 1.

As I wrote a few weeks back about “exclusive distribution channels” when it came to Spotify, Podcasts and Joe Rogan, when you go “exclusive” you artificially limit your upside. Disney essentially opted for the same path here. The problem was their exclusive channel doesn’t look to be worth it. Essentially, TVOD would have expanded the footprint by so much that it would likely have generated more sales. So that’s my number 1 option to maximize revenue. (And a lower price I think would have further convinced folks to buy it.)

What about the new subscribers Mulan brought in?

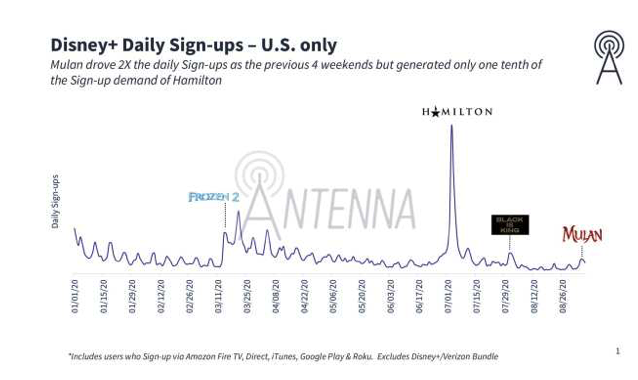

Uh, look at the Antenna data of new sign-ups in context of past releases:

In other words, Mulan didn’t drive new subscribers. Because it was PVOD, fundamentally, it didn’t help with retention either. The number of new subscribers is barely statistically significant.

What about releasing in theaters?

Unlike Universal, Disney hasn’t been expressly antagonistic to theater chains. (Though as soon as AMC and Comcast agreed on a deal, they publicly became best buddies again.) So assuming Disney could have sold the theater chains on it, yes there is a chance they could have released Mulan in theaters followed by a simultaneous or 3 weeks later PVOD release. That would have made more money than PVOD only.

The logic for me is simple: give multiple options for customers to watch a film. The challenge is most theaters in huge markets are still closed. It’s that uncertainty that is hurting theaters more than anything. And the theater chains would have fought fiercely.

Could Disney have held it until next year?

They could, but three things are holding them back. Which I’ve been struggling to explain all summer, and think I just figured out.

First, the financial cost of capital. Which is the idea that if you spend $200 million to make a film, the goal is to eventually make $216 million accounting for inflation since the entertainment industry’s cost of capital is roughly 8%. (No matter what else you know about entertainment, that’s the key math.) If you wait a year, you need to make 8% extra to cover the costs of the delay. That’s the damage “cost of capital” does to a cash flow statement.

(Want an explainer on net present value/the time value of money? Go here.)

For big films, this is clearly worth it; smaller films it isn’t. If the next Fast and Furious film does a billion dollars, taking the 8% cost of capital hit is better than a 60% total revenue hit. Using this logic, Disney should have moved it back.

The second cost, though, may be the real driver. That of what I’m calling “organizational” cost of capital. If everyone moves their films back simultaneously, the problem is many of those films can’t release at the same time. And that means you can’t start making new films, since they won’t have anywhere to go.

But that organizational “machine” wants to be working. Think of a studio–all the people, processes and what not–as a giant machine. Its output is films and TV series. The question is: what is the cost of keeping that machine idle?

It’s not zero, but add up all the headcount, lease costs, and you get an idea. Even if the cost is actually reasonable, the behavioral economics/organizational behavior implications are the machine wants to go back to work. Hence, holding every film for 2021 is infeasible.

The third reason is Disney’s SVOD schedule. They want big blockbuster films on Disney+ because they’ve already seen just how well they do. (Netflix saw this too, which is why they’re bidding on Universal, Paramount and Sony’s output.) Getting Mulan this fall on SVOD to hopefully boost Disney+ subscriber number in their fiscal Q1 applies too.

So why not release Mulan straight-to-SVOD then? A la Hamilton?

Because the numbers aren’t very good? As I wrote previously, most industry analysts who argue that all films should go straight-to-streaming (or that Netflix has a secret winning model) tend not to focus on the actual economics. They focus on top line revenue, phrases like disruption or just appeals to “the future”.

If Mulan had gone straight to streaming, more customers would have watched, but they wouldn’t have paid any more. In other words, why not get $150 million in PVOD revenue if it’s just sitting out there for you? You’ll get the SVOD benefits in three months either way.

I get it, but you’re forgetting about Disney+ subscribers. What about the “additional Disney+ subscribers?

I’ve written on SVOD economics for films twice before, and it’s worth reading either take. Here’s why:

Most back of the envelope math on SVOD films is WILDLY optimistic.

Or it breaks cardinal rules of accounting, like double counting customers. Never double count customers!

That’s the challenge with Mulan whenever it comes to SVOD. Sure, maybe 5-10 million folks will watch it on Disney+ in a straight-to-streaming scenario. So do we count all of their monthly prices as attributable to Mulan?

No!

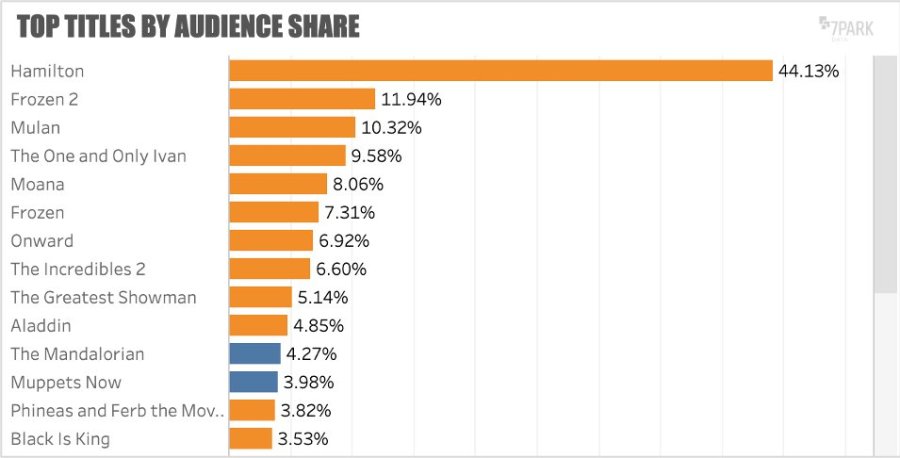

Look at this usage chart from 7 Park:

It turns out that The One and Terrible Ivan did almost as well as Mulan. Sure, it’s free, but why not attribute all their customer lifetime value to that film versus Mulan? If you start portioning every viewer to every film the watch, you run out of customers.

That’s why when I attribute SVOD economics, I am VERY conservative. It turns out that what the math says too. In other words, each film a subscriber watches over their entire viewership adds up to them wanting to resubscribe. For lots of folks, that’s The Mandalorian. Or kids binging Frozen 2 over and over and over and over and over. (You can tell my age range at my house.)

End of the day, if Mulan had gone straight-to-streaming, it would have been number one on Disney by an even bigger margin. Then it would have faded. Meaning very few folks could be attributed to it, unlike say a monster hit like Hamilton earlier this summer or Game of Thrones on HBO.

Should Disney have released Hamilton in PVOD?

It probably would have done better than Mulan. That much is clear. Hamilton is a juggernaut. Though arguably, even it would have made more money overall if it had been released next year. (It depends on just how packed the theatrical calendar ends up.)

The challenge for me is still whether or not a PVOD window in Disney+ makes sense. And long term, I don’t think it does. The PVOD window provides a confusing value proposition for customers. Why have a Disney+ subscription if they have this bizarre add-on window? Or if every film comes to Disney+ in 90 days, why not just wait?

So what about Tenet?

I’m probably being too positive towards theaters, but unlike PVOD, the theater answer is still being answered. Whenever Tenet comes to the Arclight, I’ll probably go see it. Even ignoring theaters, though, I think it’s likely that Tenet will be the top TVOD release the week it comes out, and that could easily surpass Mulan in revenue. It will basically be the biggest TVOD release since Trolls: World Tour and more widely available than Mulan. (It still hasn’t been confirmed if Mulan is going TVOD.) Thus, if you add up “Mulan PVOD + TVOD” versus “Tenet theatrical rentals + TVOD”, Tenet could make more than Mulan. Meaning they made the right call. (And maybe then Disney should have done that strategy as well.)

Clearly, the global release strategy worked, as well as a film could. It will make about $325-350 million worldwide. The problem, again, is the US and the uncertainty. If the US had led the world in testing, tracing and containment, we’d be telling a different story.

Could Warner Bros have waited on Tenet for next year? Yes, but they are running into the same issue as Disney. HBO and HBO Max need blockbuster films to thrive. (A neglected but crucial programming strategy of HBO going back to the 1980s.)

Will all this change the future of theaters and theatrical attendance?

Yes and no.

The yes hinges on whether the big chains can survive. Like debt-laden AMC Theaters. Moreover, most theaters were rolled up in big industry mergers, which has hurt innovation/quality/value creation. If they can’t make it through 2020, then yes this impacts the future of theaters.

But no, it won’t.

I tried to call this “the asterisk extraordinaire”, but the alliterative “Covid Caveat” fits better.

In other words, when looking at this data, the Covid Caveat throws out almost any conclusion you can draw. There are questions of when things will get “back to normal”, and how that normal compares to pre-Covid Caveat times, but learning lessons from within a global pandemic cum recession isn’t a great data source to plot future strategies.

What is the future of big blockbuster films?

I think they’ll be fine, but 2021 is the year to watch.

The studios make too much money from the hits to let the revenue window of theaters go completely. If the uber-packed 2021 slate does entice customers, we may see a banner year in filmmaking. Of course, the Covid Caveat applies: When is a vaccine widely available? How quickly is it distributed? Or will countermeasures work to slow the spread?

In all, we have a lot to keep monitoring. But going straight-to-PVOD or streaming alone won’t do it.