(This is another entry in a multi-part series answering the question, “Who will win the battle to make the next Game of Thrones?” Read the previous articles here.)

Two weeks ago, we checked back in on the news about the contenders vying to be the “next Game of Thrones”. Let’s keep the momentum going and get right into the “People” portion of our framework. At the end, I’ll unveil my current working model for evaluating TV series.

Why “People” Matter In Every Deal

The “people” in a typical venture capital deal are the leaders of a start-up. This means the founders and the soon-to-be chief officers. Is the CEO a great technology guy, but not great at scaling? Or an operations guy who has a dynamite CTO already in place, but no marketing experience? Conversely, is the product great and so is the opportunity, but you need to replace the leadership to make the company truly succeed? (Uber/WeWork much?)

In a real world example, lots of investors in Quibi invested because of the team of Jeffrey Katzenberg and Meg Whitman. He could handle content; she’d handle everything else. (Only later did we find out they couldn’t work well together.)

As I use the “POCD framework” for evaluating TV series—a concept I dabbled with at my previous job—I’ve found the “People” portion to be extremely important. Who is the showrunner? Who is the creator? Are they the same person? Or do you need to bring in a more established showrunner to replace the creator’s vision? Does the showrunner have the ability to manager a team, or will they do it all themselves? Can the writers work with the directors to bring their vision to bring the show? Are the producers able to corral the showrunner and bring things in on-time and on-budget?

Hopefully, the answer to all those questions are positive. Meaning the creator has a great vision, the showrunner can deliver on their vision, the writers room writes great content, the directors can film it, and the production team will run everything well. The reason this is important is because, if a studio can hire the right people more consistently than competitors, they can achieve outsized returns.

Those outsized returns fall into two rough buckets. The first bucket is the “quality” bucket: Can the show runner make a good nee great show?

Well it depends. Unfortunately, most showrunners and creators are…average.

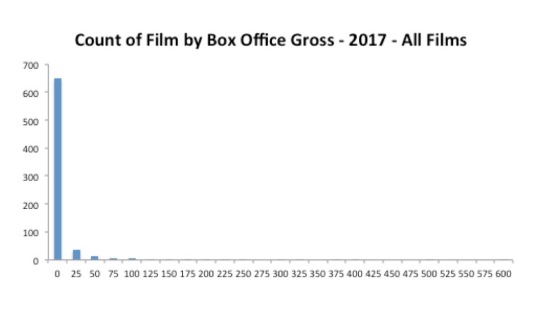

Average isn’t bad, you see. It just means that while all showrunners are great people—and indeed highly skilled at what they do—their “hit rate” is average. Which means that most of the time the shows and films they make are bombs/duds and a few times they are blockbusters. (About 1 in ten.) That’s just the math. That’s right, logarithmic distribution of returns applies to the people making shows too:

At the far right end, some showrunners can buck this trend to reliably churn out hits, but they are few and far between. Think Greg Berlanti, Shonda Rhimes, Mark Burnett or Chuck Lorre. Even then, they have more duds than you initially remember when you scan their IMDb. If either Game of Thrones or Lord of the Rings had a top tier showrunner attached, it would increase the likelihood that a show becomes a “hit” or “the next GoT/superstar” in our model. (Or if they had a top tier development exec with a similar track record. No streamer does yet.)

At the far right end, some showrunners can buck this trend to reliably churn out hits, but they are few and far between. Think Greg Berlanti, Shonda Rhimes, Mark Burnett or Chuck Lorre. Even then, they have more duds than you initially remember when you scan their IMDb. If either Game of Thrones or Lord of the Rings had a top tier showrunner attached, it would increase the likelihood that a show becomes a “hit” or “the next GoT/superstar” in our model. (Or if they had a top tier development exec with a similar track record. No streamer does yet.)

The converse to good showrunners is a chaotic leadership situation. If a show has lots of creators moving in and out and lots of directorial turnover, that’s a bad thing. (Though not always. The Walking Dead did just fine and it’s on its fourth showrunner.)

My model also punishes showrunners with extensive mediocre track records. Which unfortunately is quite a few showrunners out there. For all its admiration of experimentation, Hollywood is surprisingly conservative at decision-making. Development executives hire the same writers and directors instead of trying someone new because it’s “safer”. These showrunners produce a show for a few years that is mostly “Meh” (a technical term), and then move on to another pitch/job. In the model, if I saw a fantasy series had that type of showrunner, it would increase the likelihood that a show is another also ran TV show, not the next Game of Thrones.

The second outcome is the “logistics” bucket. Can a show come out on time and on budget?

When it comes to making blockbusters, this is less important. However, if you’re running a business, given that 95% of showrunners are average, this can be the difference between profit and loss. This can be forecast, with the right data, pretty reliably. I, for example, knew that certain showrunners and directors who worked regularly with our streamer would be late or over budget when we hired them, because they were late or over budget previously. Unfortunately, this type of data isn’t public available—studios don’t make a habit of sharing when they go over budget—so I can’t use it in this series.

It is worth noting that this was part of the genius of HBO and Game of Thrones. They managed to keep that show on every single year while being the most expensive show on television. But an incredibly efficient expensive show, if that makes sense.

(The great production houses out there—Jason Blum, HBO the last two decades, Marvel this decade—really do deliver on time and on budget, while hitting high quality bars. That’s not an accident.)

Meanwhile, most of the streamers struggle to get second seasons out within 18 months of big shows. We don’t know if these shows are “on budget” but with the way Netflix spends money, probably not? While this is important, it won’t make the model because we won’t know about financial/timing trouble until it happens.

The Results

With that explanation in mind, I’m going to be fairly conservative on evaluating these leadership teams. While picking people is really important, the benefits don’t show up on an individual show, but on a long-term/portfolio level.

Thus, I’m more worried about overvaluing “noise” than true signal in evaluating these leadership teams. (Long term, I hope to do more data analysis to better judge creative hires, but I don’t have those databases yet.) As a result, I’ll default to the “null hypothesis” more than usual.

Let’s go show by show.

Amazon’s Lord of the Ring Prequel: Patrick McKay and JD Payne

The situation most verging on “chaotic” was Amazon’s process. Amazon bought their show and went to find showrunners later. That’s like investing in a company when you have literally never met the founders. Still, it was such a big franchise they were guaranteed to find people to work on it.

In the end, it sounds like the Amazon approach was somewhat similar to the HBO approach to Game of Thrones prequel: both invited lots of writers to come in and pitch their concepts, then the development executives picked the ones they thought would do best. After those processes, we can ask, did either network pick a guaranteed winner?

Nope.

The Lord of the Rings team of writers—Patrick McKay and JD Payne—have virtually no credits to judge. If someone doesn’t have a track record, there is no data to judge either way. They sound like busy writers—they’re working on Disney’s Jungle Book film—and got a script on the Black List. But they’re far from guaranteed showrunners. (On the positive side, they also don’t have extensive mediocre track records.)

Further, they don’t have television experience. This is a red flag for me, from a development perspective. TV operates at a different pace than writing a film screenplay. Amazon has compensated for this by surrounding the team with lots of high quality writers and at least one creative from Game of Thrones (Bryan Cogman), but it’s a concern.

The obvious analogy here is the original Game of Thrones duo. Benioff and Weiss didn’t have extensive histories before GoT or even TV experience. And they produced the biggest show of the decade. Which is why McKay and Payne have the same odds as producing the next GoT as Benioff and Weiss did before GoT came out.

(Be careful of the logical trap: Benioff and Weiss not having credits doesn’t make a show more likely to succeed. Plenty of first time showrunners fail too! We just don’t remember them. That’s the availability heuristic at work.)

As for production, it’s a big “we don’t know”. Amazon has never proven it can deliver big budget shows on regular schedules, unless they have co-production partners like Sony TV. (The Tick, The Boys and their upcoming Wheel of Time series are all Sony co-productions.) Meanwhile, they do have multiple co-producing partners from the Tolkien Estate to New Line. Multiple cooks can spoil the broth.

End result? This team isn’t superstars or mediocre.

HBO’s Game of Thrones Prequel

What makes HBO great? They will say no to creatives.

HBO cancelled a prequel series to Game of Thrones the same day it announced a new prequel series. Imagine Amazon, under the pressure to get shooting within two years, deciding to scrap the Lord of The Rings project if the initial episodes end up, well, sucking. Imagine the same thing at Netflix; does it seem like they’ve ever cancelled a project?

Yet, part of what makes HBO “HBO” is they know when to say no. Even to top talent. Instead of forcing a bad Game of Thrones prequel on the world, they pivoted. (They did the same after the original GoT pilot, reshooting most of it and recasting multiple roles.)

Does this mean HBO has picked the right showrunners for their House of the Dragon prequel? Like Lord of the Rings, it’s a “we don’t know” answer as well. The lead showrunner—Ryan Condal—has run one previous show that was perfectly “meh”. His show Colony on USA Network ran for three seasons, but saw decreasing ratings each season with no “streaming” bounce. Still, that’s not a track record of mediocrity, just one show that didn’t soar. That’s not a track record of success by any means, but also not a worry.

(Fun side note: all these showrunners have ties to Lost. Condal through Carlton Cuse and McKay and Payne through JJ Abrams. Future article idea: every TV show is 6 Degrees of Separation from Lost.)

As for production, we know HBO can do that, and will likely import as many subject matter experts from Game of Thrones as they can. (Sure, the showrunners were burnt out making the show, but many, many producers, costumers, designers, directors, and what not still want steady paychecks.) This is a point in HBO’s favor.

But not enough to change the model. Again, the null hypothesis is the creative teams are “just fine” until they prove otherwise. That’s the same here. However, I will likely keep the budgets lower at HBO compared to Amazon, since HBO has proven they can keep costs down.

Netflix’s The Witcher

That just leaves The Witcher. But we don’t need to guess if show runner Lauren Schmidt can make good TV, since it came out. And it was wildly popular, with an 8.2 IMDb and 92% audience score on Rotten Tomatoes. Can she sustain this success into season 2? That remains to be seen. (Many TV creators deliver awesome season ones that drop off into season two.)

Still, when it comes to clearing the “make good TV bar”, Netflix has a hit on their hands, which means they have a good chance to get the next Game of Thrones.

Where Does This Go in the Model?

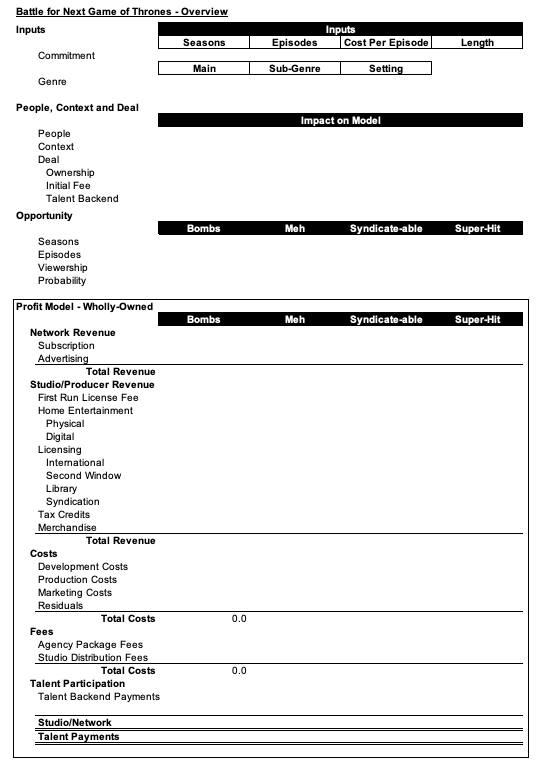

Now that we built our “TV profit model” last year, we need to combine it with the POCD model. Here’s what I’ve come up with.

Yes, that is complicated, and I’ll explain it in gory detail in future articles. And while today’s article was a bit of a let-down–there was no change to the model–it is still a key step to perform. (Getting the right showrunner can almost guarantee a syndicate-able show.)

And I promise, the next step will be fun. Which is quantifying the middle section: What is the opportunity of making a big, genre show that is “fantasy”? And that will require some data analysis.