(Welcome to my series on an “Intelligence Preparation of the “Streaming Wars” Battlefield”. Combining my experience as a former Army intelligence officer and streaming video strategy planner, I’m applying a military planning framework to the “streaming wars” to explain where entertainment is right now, and where I think it is going. Read the rest of the series through these links:

An Introduction

Part I – Define the Battlefield

Defining the Area of Operations, Interest and Influence in the Streaming Wars

Unrolling the Map – The Video Value Web…Explained

Aggregeddon: The Key Terrain of the Streaming Wars is Bundling

The Flywheel Is a Lie! Distinguishing Between Ecosystems, Business Models, & Network Effects and How They All Impact the Streaming Wars

If Disney+ has done nothing else, it has given the Disneyphiles tons of extra documentaries to consume. Making of Disneyland here. Insights into props here. More behind the scenes here.

My wife and I have watched some of “The Imagineering Story” documentary and there was a tidbit in the first episode about Disneyland’s launch which has stuck with me:

Disneyland was profitable by the end of the first year.

To compare Disney to the company that led the introduction to last week’s article, if Amazon opens a “BezosLand” in Seattle, do you think it would make money in its first year?

Heck no!

It would probably never make money. It would be created as a unique bonus for Prime subscribers who could attend for free. We would never find out how much money they make and if there were rumors BezosLand was losing billions every year, they’d leak to a few favorite journalists that the “data” makes it all up for them in selling more socks.

It feels quaint what Walt Disney did in the 1960s: He saw a way to create value—have amusement parks that were clean and cutting edge that emphasized decades old beloved characters—and when he launched it, he was quickly proven right. This is capitalism at its finest: for his bet he earned lots and lots of money. Shareholders still are benefitting from his foresight.

Far from being quaint, Walt Disney was actually on to something. For most companies making money is key. This is true even in the streaming wars. But we’ve lost sight of that fact because so many companies entering the streaming wars with plans to lose oodles of money doing so.

This is part II of my three part exploration of “flywheels” in the streaming wars. Last time I defined my terms. Next time, I’ll use the principles of this article to look at a few other new streamers. Today, the lesson is all about why making money still matters, even in streaming. And Disney’s future is the case study.

Summary

– The best way to evaluate any business is still Net Present Value.

– Even in flywheels and deficit-financed business units, the goal is still the same: to invest money in net present value positive endeavors.

– The risk of a “flywheel” with a deficit-financed component is that you simply lose money, not start the flywheel spinning.

– Disney provides the case study in this: if streaming can’t/won’t make money, their flywheel of toys, parks and resorts won’t make up for it.

– Thesis: The best business model makes money at every point, not “flywheels” that lose money in one area to make money in others. This is actually the forgotten lesson of Walt Disney.

A Reminder about Net Present Value

Fortunately, the key to evaluating flywheels is the same as the key to evaluating all businesses:

Net Present Value

Or NPV. The short hand for calculating “net present value of the discounted future cash flows”. That’s a finance-y way of saying that a company should invest in businesses that promise to make money. Again, we’re talking Finance 101 here. But it’s worth repeating because I’ve seen many businesses or ventures praised in the streaming world who likely won’t make money, even on a net present value basis. (They use narratives, not numbers. And strategy is numbers.)

Read my explainer for this concept here. (And no website can do it justice, you really should read your finance textbook to understand the details.) But for a reminder, since I use it a lot, 90% of NPV decisions look like this:

– You invest a lot of money at the start. (Capital expenditure)

– You slowly start to make some money. (Revenue)

– You still have some ongoing costs. (Cost of goods sold.)

– You subtract the two, and keep the remaining. (Profit)

– You take those future sums and account for the time value of money. (Discounting)

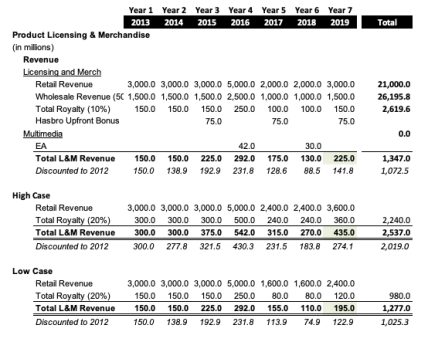

Since we’re talking Disney, here’s a look at my big series on how much they made from Star Wars toys:

The problem I keep running into with streaming video is folks seem very willing to ignore these two core principles when evaluating the streaming wars. Most money losing/unknown streaming or digital video ventures are excused because frankly we don’t know. Since we don’t have the numbers—and it’s hard to calculate them—we use narratives instead.

The problem I keep running into with streaming video is folks seem very willing to ignore these two core principles when evaluating the streaming wars. Most money losing/unknown streaming or digital video ventures are excused because frankly we don’t know. Since we don’t have the numbers—and it’s hard to calculate them—we use narratives instead.

If you take nothing away from this article, remember that even a flywheel can be evaluated on NPV terms. It’s components can, nee MUST!, be evaluated on NPV positive terms as well. Otherwise, companies run a huge risk.

“A License to Lose Money”: Explaining Deficit-Financed Business Units

Consider:

– Prime Video (money made unknown) isn’t around to make money, but to sell more socks, thus spoke Jeff Bezos.

– Apple TV+ (will spend $6 billion on content) isn’t around to make money, but to sell Apple devices and Apple Channels.

– AT&T (will spend at least $3 billion on HBO Max) isn’t around to make money, but to sell more cellular subscriptions.

In these cases, the explanation is that video is a means to an end. At extremes, defenders of the “lose money in media to make money elsewhere” even call it a “marketing expense”.

It’s worth dwelling on the concept of “marketing expense” more. Because in the previous world—the old fashioned/traditional business world—it wasn’t like you could just label something as marketing and spend as much as you wanted on it. Indeed, marketing was always taken out of your operating profit. So the more you could trim marketing while keeping sales the same, the more you trimmed! That’s why advertising is the first thing to go in an economic downturn.

Despite the branding as marketing expenses, there is real money being spent on video. These are real products from real business units. Not simply “marketing”. We need a new name, which is why I’ve come up with:

Deficit-Financed Business Units.

DFBUs. Yes, I was in the Army so I acronymize everything. It’s worth unpacking the phrases to see why these definition makes so much sense.

First, a venture is “deficit-financed” if the plan is to never make money on it. Or to make money, but so far in the future that current financing is still net present value negative. Thinking about this abstractly explains why. Say I offered you a billion dollars a year starting in 2050. The key is you have to pay me $20 billion now. Should you do it? Heck no! You could just invest that $20 billion and probably double it multiple times before 2050, making more than enough to pay yourself $1 billion per year.

That same scenario is a microcosm of “net present value”. Should Apple invest $20 billion right now to make $1 billion a year in 2050? Heck no! Just keep it in cash or cash equivalents. No matter if it is marketing.

Second, I like business unit because it really distinguishes between streaming video companies and a marketing expense. Plopping down several million dollars for a Super Bowl ad could be a net present value negative decision. (And should be evaluated in those terms.) But we should distinguish from genuine efforts at marketing versus creating brand news businesses, that in most other contexts would need to make money.

The Riskiness of DFBUs: You Don’t Make Actually Make Money on the Flywheel

My worry for companies and investors is that they don’t insist on looking at these business ventures with an NPV lens. As a result, DFBUs become a license to lose money for big tech companies. They may even grab market share—that’s certainly the case with all of them—but that doesn’t mean they actually make money.

That license usually has a justifciation, though. If we lose money on this part of a flywheel, can it make more money elsewhere? In other words, the key question is:

Can Deficit-Financed Business Units Turn a Flywheel?

This is really the supposition that has fueled the rise of streaming video. If you have a true flywheel or ecosystem, getting more customers in will help cause it to spin. That’s expressly Jeff Bezos’ logic. Apple’s too. AT&T even.

The answer? Maybe. It depends on the flywheel.

My thesis is that they can, but they are risky and hence rare. Losing money is easy for a business to do. Allowing someone to lose money means they will. It makes their thinking sloppy. Moreover, it’s easy to get the tradeoffs slightly wrong, and you deficit-financed business unit just becomes a money losing hole.

And I think I can illustrate this with Disney. If you’ve been following me on social, you’ll know that my household has been into Disney’s Inside Out recently. Which is appropriate to call back to, for this scene:

That’s how I’d describe DFBUs, they’re shortcuts that should be labeled danger. The current danger-disguised-shortcut facing Disney is losing money on streaming (Disney+, ESPN+ and Hulu.) to make it on extra toy sales. The rationales I’ve seen justifying Disney’s move into streaming reinforce this money losing narrative. I’ve seen the same arguments used by the tech conglomerates trotted out for the House of Mouse. For example, I’ve seen Disney’s streaming efforts explained as…

– They’ll lose money on streaming to get folks into the “ecosystem” of theme parks and toys.

– Disney has a flywheel and streaming video will bring more subscribers into the flywheel.

– Disney should disrupt the theatrical business model to own the customer relationship in streaming.

So all the buzz words. Of course, since strategy is numbers, the question isn’t what narrative you employ to justify losing money, but whether or not the investment will make it up in the long run. So let’s quantify—for what I think is the first time on the internet—the actual numbers behind those narratives.

The Messy Financials of Disney

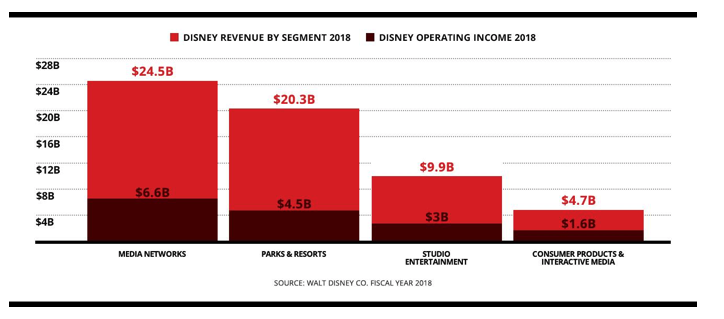

One of the first explanations for Disney’s push into streaming was so it could “sell more toys”, just like Jeff Bezos sells more socks. But take a gander at this Hollywood Reporter image I love trotting out:

Toys—from here on “consumer products”—is a small, small part of Disney’s overall operating margin, isn’t it?

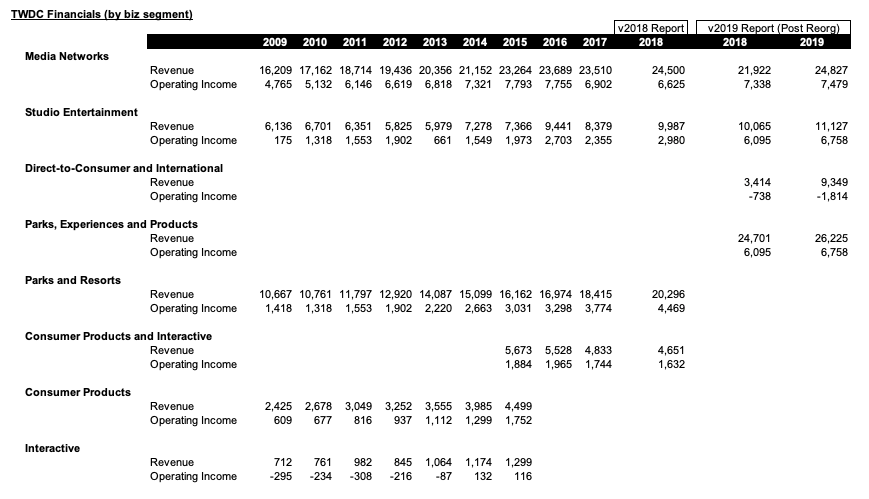

Let’s dig deeper. I approach a company’s financials like a hostile witness on the stand. What are they trying to hide? What don’t they want me to know?

For Disney, I looked at their financials going back to 2009. And a huge red flag jumps out, which should be a clue for the quality of the toy business:

For a long time, Disney separated out “Consumer Products” and “Interactive”. Then it combined them because they were shutting down Interactive and focused on licensing. Fair enough, but then when they merged with Fox, they merged business lines again, combining “Consumer Products” with “Parks and Resorts” into a new, unwieldily named “Parks, Experiences and Products”.

Why would they do this? Well, probably to hide how poorly consumer products is doing overall as a business. This isn’t a big secret: the toy industry has been severely hurt by digital disruption as kids spend more time with screens. Even if it’s doing fine for now, the worry is it will start to decay in the future. Meanwhile, Parks and Resorts remains a strong business. You can see this in the numbers. Here’s Disney’s revenue for the last ten years:

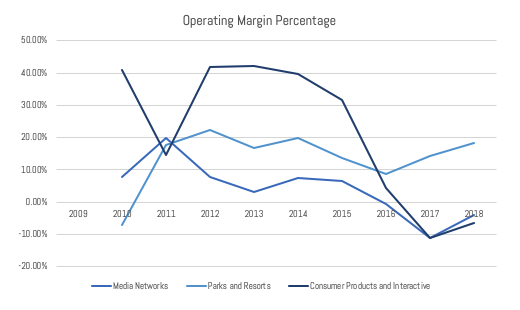

Of course, what matters isn’t just your revenue you bring in, but the operating margin you make off that revenue. Here’s the growth picture for that.

This probably shows it about as well as you can. Media Networks really aren’t a growth industry and are beginning what is likely a long term decline. But it’s not like Consumer Products are making up the gap for Disney. (And like the mid-decade boost had more to do with Star Wars joining the fold than the core fundamentals of the toy business.) What about Parks and Resorts? Sure, they’re growing reliably, but not explosively. (I left out Studio Entertainment because it’s very noisy year to year.)

This probably shows it about as well as you can. Media Networks really aren’t a growth industry and are beginning what is likely a long term decline. But it’s not like Consumer Products are making up the gap for Disney. (And like the mid-decade boost had more to do with Star Wars joining the fold than the core fundamentals of the toy business.) What about Parks and Resorts? Sure, they’re growing reliably, but not explosively. (I left out Studio Entertainment because it’s very noisy year to year.)

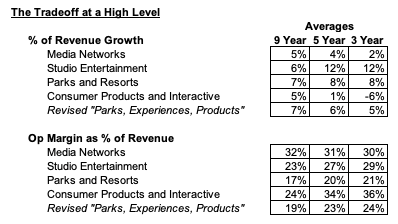

What this boils down to is a tradeoff. Which is a “Net Present Value” decision. Disney can replace Media Networks profit with Streaming profit. And that may result in more Parks and Consumer Products sales. And there is a chunk of cost in launching a a streamer. To figure out if this makes sense quickly, look at the various revenue growth rates, and the trends in operating margin from that revenue:

Normally, this is where most articles stop. After posting a few tables/charts, you look at them and draw some insights.

But we’re going deeper. Bring on the NPV scenario planning!

The Bad News for This Flywheel: If Streaming Can’t Make Money, Disney Can’t Make Money

The challenge that should leap out isn’t about replacing media networks with Streaming profit. Instead, the worry is for those advocating replacing all Media Networks with a money-losing streaming business. In that case, based on these numbers it doesn’t like like “Parks, Experiences and Products” alone can replace the revenue.

In other words the flywheel won’t make money. And that’s bananas.

This is where NPV comes in. We can chart out say 10 years of Disney financials to see how the various scenarios net out for Disney. This isn’t a rigorous prediction of Disney’s future, to be clear, but playing around with numbers of various scenarios to see how realistic they are. These tables will be small, but pay attention to the green number. That’s the “profit” correlate in these models.

My method is to take some current revenue growth rates and extrapolate them in the future. Then I made Operating Margin a function of that growth also based on historical rates. Then I came up with three quick scenarios.

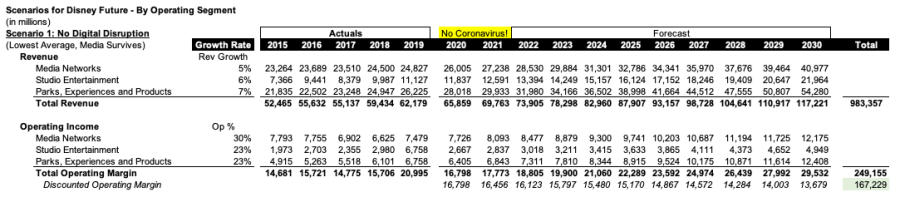

To start, imagine a world where Netflix never disrupts the TV landscape. Say cord cutting still happens, but won’t in the next ten years. What does that look like for Disney?

In other words, from now until 2030, Disney could make $167 billion dollars for shareholders if streaming had never happened. This in some ways is our baseline.

(By the way, in these scenarios I’m putting in a “coronavirus” asterisk and building the models as if it were 2019. Before we knew what would happen. Since the decision to launch a streamer predated Covid-19 this is fair.)

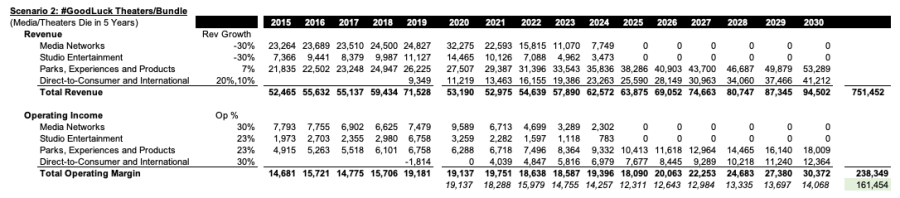

What’s the alternative? Well, the “total disruption” plan. Say streaming really does kill theaters and media business over the next five years. How does that look for Disney?

This is interesting. In the wildly optimistic scenarios where Disney grows its streaming business by 20% for the first five years, then 10% after that, it would be about $6 billion short of the “no disruption” scenario. (Which is funny for stock price reasons. Essentially, disruption will cost Disney money, but before coronavirus their stock was trading at highs.)

This scenario is also fairly unrealistic, at least in my opinion. First, theaters and media won’t die that quickly. Streaming also won’t grow that quickly. To get revenue in 2030 to $41 billion means 171 million customers paying $20 a month to Disney, which is probably too high. Most egregious, though, is the margin. I used a 30% margin to calculate the operating margin. But right now everyone is losing money on streaming. They certainly are demanding such great margins.

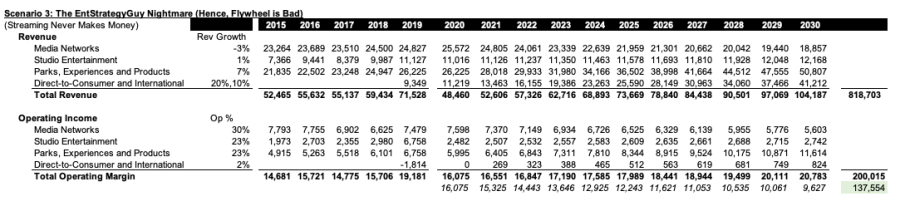

Which brings us to the third scenario, the scenario where Disney loses money on streaming. So let’s make that our last model. What I call my “Flywheel Nightmare” scenario that has a more realistic decay for theaters and networks and turn streaming from cash cow to deficit-financed business unit:

This is what happens if you “lose money” on streaming to make money on toys, you lose even more money. In a disrupted world, Disney loses $30 billion compared to a “no disruption” future. That’s outside the margin of error. In other words, even if they successfully enter the streaming world, they’ll be worse off financially than a world where disruption had never happened.

This all ties back to the flywheel concept. Frankly, if one pillar of your flywheel loses money, then the rest of the flywheel has to work that much harder to make money to justify it. And this is the key insight.

There Has to Be a Better Way!!! Walt Disney Showed Us a Better Plan

I’ve used Disney as the example in today’s article because frankly Walt Disney understood a better system than risking his company’s profits on money-losing ventures. You’ve all seen it, but it’s worth trotting out Disney’s map of how it’s various business units worked:

Note, despite what you’ve read, this isn’t a flywheel! Every conglomerate could draw up a similar chart with connecting arrows. Walt Disney merely mapped—in great form because he’s a terrific illustrator—how every business unit at Disney works together.

Meanwhile, most folks look at this and misunderstand the core point. Disney, the man, expected his company, Disney, to make money on every part of his plan.

That’s right, whether you call this an ecosystem, flywheel or set of business units, Disney’s devious plan was to have each business make a profit. While building up the brand of its various franchises.

That’s the lesson for Disney+. The way to make more money for Disney is not to emulate its peers free cash flow losing models (Netflix, probably Amazon, definitely Apple), but to be the streamer that makes money on streaming while making extra money on every part of the value chain. That’s how you become a free cash flow generating monster.

Frankly, I think Bob Iger knows this, which is why I’m still bullish on Disney overall. I just don’t buy the bad narratives explaining it.