(This is Part VII of a multi-part series answering the question: “How Much Money Did Disney Make on the Lucasfilm deal?” Previous sections are here:

Part I: Introduction & “The Time Value of Money Explained”

Appendix: Feature Film Finances Explained!

Part II: Star Wars Movie Revenue So Far

Part III: The Economics of Blockbusters

Part IV: Movie Revenue – Modeling the Scenarios

Part V: The Analysis! Implications, Takeaways and Cautions about Projected Revenue

Part VI: Disney-Lucasfilm Deal – Television

Part VII: Licensing (Merchandise, Like Books and Comics and Video Games and Stuff))

If you’ve been reading along after 47 pages and six months of writing, you know that Disney more than made its money back on its purchase of Lucasfilm through releasing wildly successful Star Wars sequels, and then making another $1.7 billion in licensing revenue. So they made their money back.

But to truly get a great return on investment—as I wrote in the introduction in my “gut” section and again when referring the licensing & merchandise—theme parks are the whipped cream and cherry on top. In 2019, if it stays on track, in Disneyland and in Disney’s Hollywood Studios, Disney will open Star Wars: Galaxy’s Edge, which have been under construction since 2016.

And they could be huge money makers.

Theme parks allow The Walt Disney Company to make more off its IP than any other studio. (That’s its competitive advantage.) So let’s figure out how to quantify that benefit. Then, we’ll figure out the costs.

The Challenge: Disentangling the Marginal Benefit of new Theme Parks

With movies, calculating the revenue is messy, but we have lots of data. With toys, forecasting the revenue is easy, but we have way less data. What about for theme parks? In this case, the toughest part of the process is assigning the value.

Think of it like this. We know that putting in a Star Wars: Galaxy’s Edge at Disneyland will drive attendance and revenue. The problem with theme parks is untangling how much revenue they will drive.

In other words, the “marginal benefits”.

Some day I’m going to write “Marginal Benefits Explained!” because it’s a core economic principle—the core principle?—and I’ve seen 7-figure-earning business execs screw it up. Marginal benefits are the additional revenue a business generates by changing an input. So if you’re making a million dollars a year and raise prices, and it goes up to $1.2 million, your “marginal benefit” for the price raise is $200K, the additional revenue you generated.

(You want to know my biggest frustration/pleasure with this website? Every time I write a new article, I think of two more posts to write inspired by it. The “hydra problem” of the Entertainment Strategy Guy.)

This idea is what stymies the analysis with theme parks. Let’s visualize it with an example.

Next year, I’ll walk into Disneyland in the off-season (probably September-ish). I’ll be wearing a Star Wars shirt. My brother will probably rock a Marvel shirt. That said, I’ll also have a three year old wearing, if current trends hold, either an Elsa (Frozen) or Belle (Beauty and the Beast) dress.

So how much of that trip do you allocate to the opening of Galaxy’s Edge? (Punctuation side note: do you italicize theme park lands? I did, but should I?) My family already averages one trip to Disneyland every year, and my daughter knows that Mickey lives at Disneyland. So she’d go anyways. But what about me? I’ll definitely go to see the new park at some point. We could make an analogy of a theme park to a content library on a streaming platform. People pay for the whole thing, not the parts. With content libraries—which is essentially what a theme park is—untangling and clarifying the value offered by each piece can be tough.

The Economics for Theme Parks

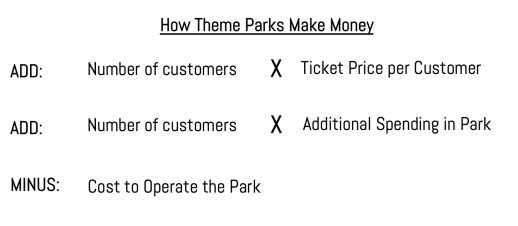

When in doubt, I like to boil things down to a simple formula. So let’s do the rough “business model” for a theme park. I came up with this:

I hear you. What about hotels? What about transportation? What about infrastructure? What about marketing partnerships? Sure, it gets more complicated, but at the end of the day that simple formula is how you make money.

However, that’s the rough total value of a theme park. The value of Star Wars: Galaxy Edge obviously isn’t that entire formula. There’s a baseline of people going to Disneyland every year even without Star Wars, as my hypothetical above showed. Not that Lucasfilm didn’t have a presence in Disneyland: there are two rides (Star Tours and Indiana Jones Adventure) and an incredible show (the Jedi Training Academy) and Star Wars has invaded the park since the merger.

So adding a new Star Wars park is valuable. Obviously, but how valuable. Well, the key is the lift in the numbers, which is the marginal benefit. The additional money made. So…

Let’s just work through the formula to put a value on those marginal benefits. First, I’ll review what we know. Then what we can assume. Then we’ll make some estimates for how to attribute value.

Let’s just work through the formula to put a value on those marginal benefits. First, I’ll review what we know. Then what we can assume. Then we’ll make some estimates for how to attribute value.

What We Know

Visitors

The visitors numbers were fairly easy to find. An industry trade group releases numbers of visitors per park for all its members, and Disneyland owns the top parks. Here’s the annual visitors to Disneyland and Disney’s Hollywood Studios (where Galaxy’s Edge will land in Orlando): I also found an article that claims that Disneyland has about 1 million annual passport holder, which I assume makes it into the numbers above. That said, if they use their passport frequently, then our price numbers may be slightly lower. Again, it probably averages out and is too small a detail to really throw off our averages.

I also found an article that claims that Disneyland has about 1 million annual passport holder, which I assume makes it into the numbers above. That said, if they use their passport frequently, then our price numbers may be slightly lower. Again, it probably averages out and is too small a detail to really throw off our averages.

The key number from the above numbers is the growth rate, which at Disneyland has averaged 1.8% per year historically. When I first started writing, the visitor numbers for 2017 hadn’t been released yet, and I calculated them for Disneyland at 1.8 % through 2016. Then 2017 had a growth rate of…exactly 1.8%. So that number feels solid. At Disney’s Hollywood Studios, they’ve averaged 1.3% per year.

This is also a good time to point out that Disneyland in Anaheim and Disney Hollywood Studios in Orlando have different economics. Basically, Disneyland has had climbing visitor counts and ticket prices for years, even without a new Star Wars land. (Though, again, a lot of Star Wars tie-ins since The Force Awakens.) Disney’s Hollywood Studios has not. If you search, “Disney Hollywood Studios empty” you find results about how no one visits that park. So Disney’s Hollywood Studios has a lot more potential visitorship (a word I made up) to gain. It opened a Toy Story Land recently and Star Wars: Galaxy’s Edge will help boost visitorship.

Ticket Price Increases

The constraint for a theme park like Disneyland is space; there just isn’t any more room to put the additional people who want to go. They’ve essentially maxed out on visitors coming each year, or nearly have. Moreover, Disney’s goal in the parks is not to increase viewership per park too quickly because it will lead to a worse customer experience. But they can still make money off this pent up demand. This chart form the Orange County Register pretty much sums it up for Disneyland: they’ve slowed visitors growth by sky high price increases. Here’s a chart from the Orange County Register.

The rate of price increases on tickets can seem eye-popping. At first blush, the price of the most expensive ticket at Disneyland went from just $43 dollars in 2000 to $135 in 2018. Yikes. Some cautions should slow us down on these numbers. First, I haven’t adjusted for inflation, which would lower some of the eye-popping-ness. Second, Disney recently changed its ticketing policy to move to “tiered pricing” that I would call “variable day pricing” meaning peak season tickets are higher than off-season. Here’s a chart laying out the current prices at both Disneyland and Disney’s Hollywood Studios, showing the difference. (This “All Ears” website has a great rundown of historical prices.)

The rate of price increases on tickets can seem eye-popping. At first blush, the price of the most expensive ticket at Disneyland went from just $43 dollars in 2000 to $135 in 2018. Yikes. Some cautions should slow us down on these numbers. First, I haven’t adjusted for inflation, which would lower some of the eye-popping-ness. Second, Disney recently changed its ticketing policy to move to “tiered pricing” that I would call “variable day pricing” meaning peak season tickets are higher than off-season. Here’s a chart laying out the current prices at both Disneyland and Disney’s Hollywood Studios, showing the difference. (This “All Ears” website has a great rundown of historical prices.)

The key number here is 6%, which is the combined annual growth rate of both Disneyland and Disney’s Hollywood Studios since 2011. Unlike attendance, these numbers well out pace inflation and show strong growth. Here’s our rough assumption of average ticket prices per park.

The key number here is 6%, which is the combined annual growth rate of both Disneyland and Disney’s Hollywood Studios since 2011. Unlike attendance, these numbers well out pace inflation and show strong growth. Here’s our rough assumption of average ticket prices per park. Additional Spending in the Park

Additional Spending in the Park

When you go to the park, you don’t just pay to get in, you pay to eat, pay to bring something home and pay to park. All these things add up as well. According to Vogel’s Entertainment Industry Analysis—the gold standard in financial analysis for entertainment—a non-Disney park tends to have about $20 of additional spending per person as of 2015. My guess is Disney in general does about twice that. The cost of those ears adds up.

So I looked for hard numbers to back up my gut. I couldn’t find Disneyland per spending numbers, but could find EuroDisney spending numbers. They end up projecting that the average visitor spends 54 Euros per day at the park, which gets to roughly my $40 per day factoring in the higher price of a Euro compared to a dollar. Not exact, but close.

Costs of a New Theme Land – Fixed & Variable

I found multiple articles that cite that Disney expects to spend $1 billion dollars in total construction on both parks. I’m going to average that out over the construction time period of 3 years. Further, Vogel projects that variable costs of things like employees, maintenance and electricity cost about 50% of a non-Disney theme park, according to surveys. Unlike spending in the park, I don’t see a reason why Disney’s costs would be lower, especially in expensive Sourthern California, so I’m going to keep that estimate.

What We Will Assume

Those are a lot of good facts above, but now we need to draw some conclusions to inform our model. First, the value of a new Star Wars: Galaxy’s Edge at Disneyland is to allow for prices to continue to increase. It’s not like Disneyland needs Star Wars to make it relevant. But it will continue to allow Disney to maintain those crazy double digit price increases. So when it comes to projecting growth into the future, I’m going to keep Disney theme parks CAGRs in visitors and price increases steady going forward.

Also, there is more growth opportunity in Disney Hollywood Studios. As I mentioned above, its attendance lags the other parks and so do its ticket price increases. Disney has already opened Toy Story Land, but Star Wars: Galaxy’s Edge will really help drive foot traffic. Economically, the marginal benefits of the new park will be higher in Orlando than Anaheim. To calculate this, I’m going to bump up the ticket price increases by 2% above the 6% CAGR for two years to get closer to Disneyland’s price per ticket. It’s visitors per year will also increase with the same bump since it’s been flat the last few years.

I’m going to take the “building costs” number of $1 billion and add a “cost overruns” of 20% to it. Why? Because of the project planning fallacy. It’s really hard to hit initial budgets, and Disney has a lot of reasons to round that down for investors. I’m going to put these overruns in 2019 the year the project launches.

What We Will Estimate

Now then we get to the hard part. The part where financial analysis is more art than science. I need to attribute the value of those bumps above to Star Wars: Galaxy’s Edge. As the formula shows above, Disney can make money by increasing ticket prices, getting new visitors and having those new visitors spend more in the park. It’s easy to do those calculations, but we can’t have new visitors be attributed to Star Wars indefinitely into the future. That’s giving Star Wars too much credit.

The easiest solution is to make a percentage of attribution, and apply that to each category into the future. For my model, I’m assuming that the price increases and visitor account increases are due almost solely to Galaxy’s Edge for the next five years, then it will phase out over time, decreasing by 10% each year. Again, I don’t have math or statistics for this, just my gut.

Let’s talk about this assumption, because this is the key game you play when you make a financial model on a theme park. (And yes, before Disney built this park, I guarantee you that had a hundred times more complicated financial model built off years of financial data. I don’t have that so I get to make assumptions. But man I would love to see it.) Even with that model, though, you could argue these assumptions on attribution and price increases are both “conservative” (underselling how much money Disney will make) and “aggressive” (overstating the case).

On the “this is conservative” side, I could just go ahead and assume way more visitors are coming to Disneyland and Disney Hollywood Studios than just the increase in year over year. As in a larger percentage of all visitors. Maybe attendance would have declined without this new park? Though that case seems much better for Hollywood Studios than Disneyland, since Disneyland has a base line of people who would attend no matter what happens, that would seem aggressive.. Either way, I made the same assumption for both parks.

Also on the conservative side, Disneyland started pushing Star Wars tie-ins almost immediately after the deal closed and really pushed them once The Force Awakens hit theaters, and I didn’t model any of that potential added revenue. That said, Star Wars was in the park for decades before the merger.

On the “too aggressive side”, 100% attribution for 5 years is also a big number. Disneyland will keep opening and refurbishing rides every year. In Hollywood Studios a Guardians of the Galaxy ride is opening in 2020, but I keep all the attribution for Star Wars. Weighing both sides, I am fine with how the model is currently.

The Final Model

Put those three pieces we “know” together with our “assumptions” and my estimates for attribution, and we get a pretty good estimate of how well Disney has done historically at these two parks:

Note, my model only goes to 2027, as it has for this entire project. That’s because predicting even ten years is mostly blind guesswork, and predicting out beyond it is just throwing darts. Notably, though, this model says—mainly driven by the huge upfront costs and the huge variable costs per additional customer—that Disney is projected to lose over $300 if you factor in the time value of money.

Hmm.

What gives? Theme parks were the cherry on top? Where did that revenue go?

Well, to the capital expenditure of spending $2 billion dollars (or $2.4 with my overages) on two new lands. That’s a huge investment, but one Disney expects to pay out for decades, not just 8 years in my model. The way to model that is with a…

The “terminal value”

In my first article in this series, I wrote that I’d address the “terminal value” at the very end of this project, which will be my next article (or two) in this series. Essentially, after all the revenue so far, the terminal value is the rough value of the whole franchise going forward. And that deserves an article by itself.