(This is an “Appendix article” to a multi-part series answering the question: “How Much Money Did Disney Make on the Lucasfilm deal?” Previous sections are here:

Part I: Introduction & “The Time Value of Money Explained”

Appendix: Feature Film Finances Explained!

Part II: Star Wars Movie Revenue So Far

Part III: The Economics of Blockbusters

Part IV: Movie Revenue – Modeling the Scenarios

Part V: The Analysis! Implications, Takeaways and Cautions about Projected Revenue

Part VI: The Television!

Part VII: Licensing (Merchandise, Like Toys, Books, Comics, Video Games and Stuff)

Part VIII: The Theme Parks Make The Rest of the Money)

So after a planned family vacation and an unplanned family emergency, I’m back with my series estimating how much money Disney has made on the Lucasfilm acquisition. The next place to go is movies. How much will Disney make on the new Star Wars films?

Well…

Listen, I was all set to dive into the economics of Star Wars movies. Then I realized some readers may not know how movie accounting really works (or doesn’t work?). Before I can get into the specifics of these films, I feel like I should explain all feature film economics.

Can I explain it all? Given that some professionals spend their lives working on this and books have been written on it and courses taught on it, no. What I think I can do—what I will try to do—is provide enough of a summary right now that you’ll know how I calculated the movie returns, and you’ll have an idea for how this works.

I also decided that this isn’t really “Part II” of my series. If I were writing a report on this, I’d put this section in the Appendix. You don’t have to know it to get to the conclusion, but you may want to read it. And if you don’t know it, you’d want to read it before Part II. So here is is: my explanation for how film economics works and my confidence in various pieces.

A Brief Movie Windowing Model

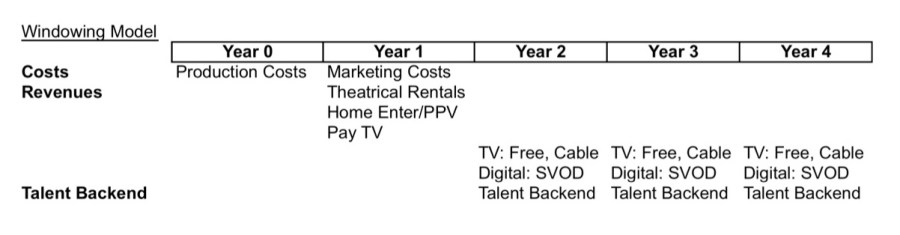

A movies’ finances breaks down into four rough areas: costs, revenues, studio fees and back end. They appear (either going out or coming in) in roughly that order, which is also important. (As I wrote in Part I about the time value of money, you can skip ahead if you know this, but you may still enjoy it.)

A note before I start. I call this a “windowing” model, but I’ve heard it called all sorts of things. If you make it before the film is released, then you’d call it a “greenlight” model. It’s called that because you forecast all the numbers to give a movie the “greenlight” to release. It’s called a windowing model because each phase comes in successive windows. Otherwise it could be called an accounting statement for purposes of talent.

Let’s start with costs. The biggest cost is making the film. Even with growing marketing budgets, a film’s biggest expense is usually the actual production cost. This is often called the “negative cost” or the costs required to get a roll of film, the aptly-named “film negative”. While we’re concerned with blockbusters here, it should be noted that the vast majority of movies come in well under a $100 million dollars in production budget. To give you an idea, using films from 2012-2014 (the best data set I have which has production budget estimates), of the 1,084 movies that had a theatrical release in that time period, nearly 95% cost under $100 million to make. This includes a huge number of independent films. Even excluding those and just focusing on major studios, 86% of their films cost under $100 million to make for the time period from 2003 to 2014 (from another data set I have).

The next biggest category is marketing expenses, which have continued to creep upwards. I’m tempted to make a joke that the only thing increasing at a faster rate than marketing budgets is prescription drug prices, but that just doesn’t seem fair…to prescription drug prices. They make up a huge amount of the budget. In an article in Adweek, it pegged the spend on average at $40-50 million per film. Again, that’s the average for all movies; for blockbusters it goes much, much higher, with The Hollywood Reporter pegging it at well over $200 million worldwide for blockbusters.

Both production and marketing costs start before revenue comes in. This isn’t captured in a film’s individual breakeven model, but does impact the returns in normal finance/the real world (the real world being distinct from Hollywood). In a lot of movie green light models, production costs start in Year 0, if Year 1 is when the movie is released.

The Star Wars movies fit this profile. They can start spending production money up to two years before they make it into theaters. For my film models, I’m having production costs start the year before a film comes out, marketing costs the year a film comes out and profits mostly in the years after. (I’m making some simplifying assumptions that aren’t as accurate as the financial statements Disney has, but will get us close enough to an answer.)

Let’s move onto revenue. And the place to start with revenue is theatrical box office. This is all the money from tickets purchased by customers to see a film in a theater. A large chunk of revenue for all movies, it is important to remember that a movie studio doesn’t collect all the money earned at the box office. That’s where the term “theatrical rentals” comes in. Theatrical rentals are what studios actually keep; box office is what they split with the theaters.

My rule of thumb here is that a studio collects usually around 50% for domestic box office (meaning the United States and Canada). The other fifty percent stays with the theaters. This has fluctuated over time as movies hang around in studios for shorter time periods and as studios like Disney play hardball, but fifty percent is a good guidepost.

For international markets, that amount varies per market and per distribution deal. From my experience and what I’ve read have, that split more is like 35% to 40% of total box office. I’m going to go with the lower number for one main reason in my model: China. China only lets studios keep 25% of domestic box office, and getting cash out of China can be difficult. So for films expecting big returns off Chinese box office, it will lower the total revenue split of theatrical films. The “domestic to international” split has been covered widely, and mainly whereas the United States used to account for 50% or more of total box office, that is shrinking over time (again, mainly driven by China) and is now more like 35-40% of total box office.

Box office, though, is just the first slice of the pie. And it’s a pretty big slice. Currently, I estimate that 25-35% of total revenue from a film comes from the theatrical rentals. Meaning of all the money a movie makes through theaters to DVDs to toys, about 30% of that is box office. This number used to actually be lower when DVD sales were boosting the whole industry, and has risen as percentage of total revenue per film as DVD sales have fallen.

So what is that other 65% made of?

All the other “windows”. I called this a windowing model because each “window” is the distribution channel that currently has the rights. It starts with theaters, “the theatrical window”, then moves to home entertainment: DVDs and electronic sell through (buying movies off iTunes and Amazon Prime and others to own). This window used to be measured in years—I still remember distinctly that Jurassic Park took over a year to come out on VHS—and has shortened over time. Home entertainment used to drive a ton of profit from the 1990s to the 2000s and even exceeded theatrical rentals for many years. As home entertainment has shrunk, the importance of theatrical rentals has increased. (Note, though, that home entertainment hasn’t completely died, especially overseas, even though most movie executives act like it has.)

Then comes the other windows. From roughly highest value to lowest, traditionally, it is Pay Per View, then pay cable, then cable or broadcast and then later runs. The one variable is streaming services. They have stepped into the gap acting like pay cable or basic cable. So really, it is pay per view, then it is “other TV and TV-like windows”. In addition, some movies, especially movies targeted at kids, can sell merchandise like clothes and toys. Back in the days when DVDs were a thing, you could also sell movie soundtracks.

There are a bunch of costs associated with all of these smaller windows, but I’m not going model them explicitly. Sure, Universal may sell a bunch of Minions toys, but that’s inaccurate. Universal doesn’t sell the toys, Mattel or Hasbro or Spinmaster sells them. Universal gets a royalty from other people doing the selling. So even if they sell $100 million in toys, they only make about 5% or $5 million on it. The same thing happens for home entertainment. Sure, Star Wars sells a ton of DVDs, but you have to pay for the disc, the packaging, some marketing and split the revenue with the wholesaler and store. And pay talent fees per disc. So you don’t end up with nearly 100% of total sales. For our purposes, we are just going to model the revenue that finally makes it to Disney. That’s really what matters, not the costs along the way.

Some quick notes on the table above. I based the core numbers on Jeffrey C. Ulin’s book The Business of Media Distribution since it is publicly available, so I’m not giving away any secrets. I cross referenced it with some other fairly reliable sources and tweaked the numbers to match my gut on industry trend. If you’re interested, it and Vogel’s Entertainment Industry Economics are two great, really in-depth reads. (If you have critiques of it or think I’m off, feel free to send them to me so I can update the model with your information.)

Some quick notes on the table above. I based the core numbers on Jeffrey C. Ulin’s book The Business of Media Distribution since it is publicly available, so I’m not giving away any secrets. I cross referenced it with some other fairly reliable sources and tweaked the numbers to match my gut on industry trend. If you’re interested, it and Vogel’s Entertainment Industry Economics are two great, really in-depth reads. (If you have critiques of it or think I’m off, feel free to send them to me so I can update the model with your information.)

Second note, I’m not counting licensing and merchandise for the Star Wars films, which is why I’ve highlighted that section. I’m doing this on purpose. Since L&M is such big business for Disney in general, I don’t want to double count it. It can be tricky to say, “This product is for the movie; this product is for the core franchise.” I’m going to project L&M revenue on their own in a later section.

Third note, obviously industry wide trends can vary per studio and per feature film. But we have to make some assumptions to get the analysis rolling (we can always tweak them later) and the Ulin numbers match what I have seen.

Final note, which is a piece of advice: heavily use “rules of thumb” when you can. I’m building a complicated (though not complex) model on Star Wars feature film performance by film. Sometimes though you don’t need that complication. Sometimes you can use one number to eyeball how something is doing. In this case, you see that if you know the total box office of a film, you can multiply it by 1.4 to get an idea of it’s total revenue. That’s useful. (And you can see that it used to be 1.9 in the past when home entertainment was propping up the business.)

Fees are the next delightful part of the movie budgeting process. In this, a studio collects “fees” from movies for both distributing and marketing a motion picture. These “fees” are ironic because I mean, aren’t you the studio? Who are you paying the fee to? Well, “not talent” is the answer. The fees are there to ensure that Fox or Disney or Warner Bros. makes a profit before talent gets paid. Makes sense, right? I’m using distribution fees of 25% and marketing fees of 20% in my models for Star Wars films. Again, this comes from a variety of sources like Ulin and Vogel, and some internet sleuthing that keeps it in that range. (Some going up to 30% for distribution, some down to 20%.)

If, despite fees, a film does make money, it pays the talent. This is our fourth area, talent backend participation. The main thing to know is that a billion dollar film—that even Disney can’t argue isn’t making money—will have to pay some of its profits to major, A-list talent. How you pay talent and how much talent you have to pay can vary widely film to film. If you’re the studio, you can model each talent agreement separately, because you know what the contracts look like. For my model, I’m going to make a simplifying assumption that all talent is paid a percent of the “profits” of a film.

When you try to combine the fees a studio receives with the talent back end, you end up, essentially with two different accounting statements. Take a look:

This is the weirdest part of the budgeting process. There are really two different models, one for the studio and one of the talent. The Studio collects its fees from the revenue as it comes in across theatrical, home entertainment and television distribution. The studio just banks this money. This is how a Studio can make money on a film that “loses money”. By losing money, I mean the profit after fees is negative. In the above example the studio made $5 million dollars, but talent didn’t see a dime because with fees the film is still $56 million in the whole. This is a simplified version of movie budgets, but definitely a common occurrence.

This is part of the reason why the “major studios” exist as a concept at all. They have huge apparatuses built to distribute movies to theaters and market them and then distribute home entertainment. Ostensibly, the fees help pay for that entire apparatus, but they also help guarantee their profits, even if a lot of their movies flop.

Also, it does matter when the costs out and revenue comes in, as I covered in Part I. The next chart shows how I modeled the various costs, as that’s roughly when they come in or go out, though honestly feature films can make money for up to 10 years after they were released. (For example, TNT is currently paying to air Star Wars films released 30 years ago and to air the current Star Wars films.) Again, I simplified; I wanted to show the impact of the biggest costs and revenues without overly complicating the model.

Reviewing the Assumptions of the Movie Windowing Model

Phew, so that’s the financial model of feature films in a nut shell.

Now, we’re ready to go from the general to the specific and really make some assumptions about the Star Wars films to guess how much money they made. For the four rough categories above—costs, revenues, fees, and backend—if we don’t work for the production company, or an agency representing the talent, we’ll have a lot of assumptions. So I want to be honest about what I know, what we can assume and what we can estimate for these films. (And if someone wants to send me a talent participation statement from any of the movies, thank you in advance!)

Costs are educated guesses. Some analysts provide their own estimates and other guesses filter out to the internet. That said, we know the scope of most big blockbusters in terms of production and marketing budgets, so we can make an educated guess within a general range. Most blockbusters have pushed their budgets past $200 million per film, with some much higher.

For revenue, the key input is almost totally impossible to forecast, but once you have that, everything else falls into place. That input is box office. If someone tells you they can forecast box office in say two years, they are wrong. But as you get closer and closer, you get more accurate. Then, once you have box office data, well you can forecast the rest of the revenues with fairly reliable accuracy. For our analysis of the Lucasfilm deal, the great thing is box office is open source, meaning we all have that data.

For all the revenue besides box office, I put my assumptions in the section above and they’re all percentages based off the box office. These guesses are assumptions, but fairly strong ones. There is some variance in the outcomes in that some movies have a “second life” in home entertainment, but the bulk of movies (90% say) fit within the model above. I could go through and make estimates for each revenue line, but honestly that would just introduce more chances to make an incorrect assumption. On average, this model works.

Fees would fall into the same category. In some cases, talent will negotiate on fees, but usually they are covered by standard terms. So overall those are reliable estimates. Backend is also based on assumptions, but it can vary per talent pretty widely, so again it’s an assumption. Overall, I’d rank the assumptions on my model like this:

Assumptions:

Revenue —> Open source, with assumptions about percentages

Fees —> Very educated estimates

Costs —> Best guesses, with some leaks

Backend —> Guesses

Initially, when I started writing Part II, I intended for the this article to cover all the financial projections for the Lucasfilm deal, including the explanation about how box office was calculated as a quick explainer. Since I’m at 3,000 words and haven’t even gotten into the difficulty in forecasting box office, well it looks like that’s moving to Part III.

Join us next time when I bring this film model into the Star Wars universe, and update my thinking accounting for Solo: A Star War Story’s lackluster opening.