Honestly, it’s either feast or famine with news in entertainment. Some weeks, I look at all the stories and can’t figure out what is the most important. Then other weeks, I have a plethora to choose from. This week fell on the “plethora” end of the spectrum.

Two stories led the pack. Quibi raised and lost $2 billion dollars. So that’s a big story. Yet, splitting up Google could have tens of billions of market moving ramifications. How do I pick when Quibi is so juicy, but Google is so important? Why, by combining the two!

(As always, sign up for my newsletter to get all my writings and my favorite entertainment business picks from the last 2 weeks or so.)

Most Important Story of the Week – Google’s Antitrust Lawsuit and Quibi’s Demise

The background, in case you didn’t hear:

– The Department of Justice under Bill Barr filed a lawsuit with 12 state attorney’s general arguing that Google is an uncompetitive monopoly in search. This lawsuit makes lots of similar arguments to the Microsoft case of the 1990s about using their power to exclude competitors.

– Quibi is exploring options to shut down, as reported in the Wall Street Journal.

So how does the former relate to the latter?

To explain that, consider a thought experiment. Imagine that along the way, Jeffrey Katzenberg pitched Susan Wojcicki (the head of Youtube) the plan for Quibi. And she loved it. (Hypothetically.) She replies, “Jeff, don’t launch Quibi as a standalone service, we’ll buy it! And you run it as a standalone venture.” Then assume they keep everything else the same. The same budgets. The same product. The same everything.

Would Quibi still be around?

Yes!!!

And the explanation is fairly simple: Google can afford $2 billion in losses over three years. In fact, Google can afford to lose $2 billion dollars every year on one business. And maybe more.

My favorite example to show this is the money pit that is Youtube TV. When it launched, Youtube TV cost $35 per month. After adding some more channels, it bumped up its price to nearly $60. And that’s every month. For nearly 2 million subscribers. The thing is Youtube was likely losing money every month on Youtube TV, and potentially still is losing money every month on that service.If Google is losing $20 per subscriber per month, then they could easily be losing half a billion dollars per year. If not more.

In other words, Google will easily lose billions on a speculative streaming venture.

This gets to the realization I’ve had debating the streaming wars over the last year or so. And it started with Apple TV+. Essentially, I’d find myself talking past folks when we discussed our opinions on Apple TV+. I’d say that I thought the lack of a library, lack of ownership in original content and unclear pricing were strategically bad decisions. Then folks would counter that it didn’t matter because Apple could afford the losses. The same arguments are made for Amazon and Google in a number of businesses as well.

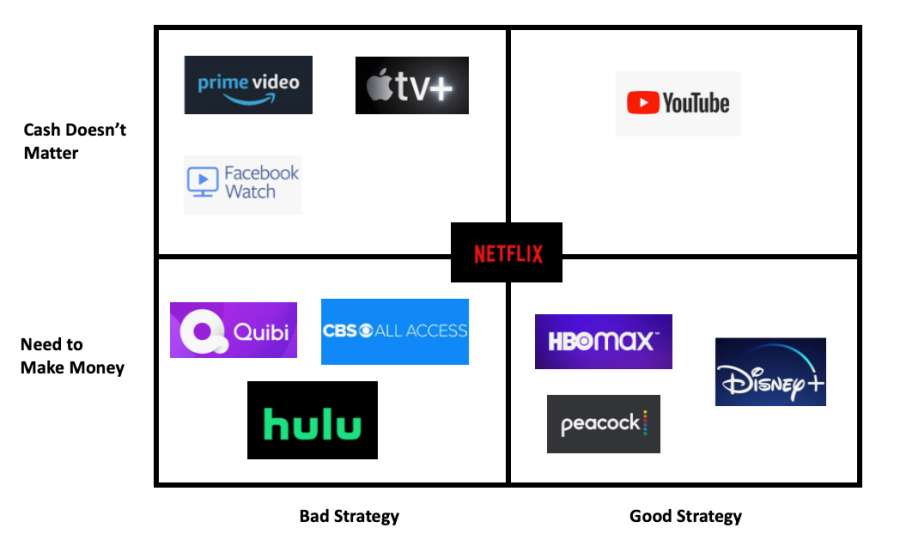

But these are two different arguments. One is about the quality of the strategy. One is about the access to resources. These two questions help frame the streaming wars. And they are two questions we should ask about every major player (from both entertainment and technology) in the streaming wars:

- Does a streamer have a good business strategy?

- Does the parent company have immense resources to allow deficit financing?

For example, I’d say that Apple TV+ has a bad strategy overall, but they have a parent company that can shield those losses. And while Prime Video has eventually clawed its way into second or third place in the US streaming rankings, it likely has lost lots of money in the process. But who cares because Jeff Bezos is the world’s richest man.

We could go on, or I could make a quad chart to give you my take on this equation:

For Quibi, a questionable strategy meant they ran out of business. For Apple TV+, who has arguably the same bad strategy (if not even more cash burn), it doesn’t matter because they can burn cash unlimitedly. Disney likely can’t afford perpetual losses. Netflix is the only firm in the middle because it’s strategy clearly worked, but it also lost tons of money. It also needs to make some money, because it doesn’t have a wealthy parent, yet some would argue the equity markets do that for them.

The lesson here is really for practitioners. The business leaders out there. Draw lessons from those with good strategy, not those who have cash resources you may or may not have the ability to match. Good strategy is still good strategy. (What is good strategy? Books are written on it, but for me it’s a product that matches the needs of a targeted customer segment that creates value over the long term, by leveraging a competitive advantage.)

Society could also take some lessons from this. The market should pick winners or losers because they have good strategies. Because that means companies are creating value. When external factors support money losing enterprises, it’s usually because they are trying to acquire monopoly power, which is bad for innovation and customers.

These are trends that Quibi tried to fight against, but ultimately failed. Too many folks are spending too much in ways that don’t require earning money for it to have a fighting chance. Whether or not Jeffrey Katzenberg and Meg Whitman should have seen that coming is an open question. And likely their business model was flawed, as I’ve written about before. But the reason they went bankrupt, ultimately, is because they didn’t have a parent company support massive losses.

This is the power of Big Tech and while the current antitrust lawsuit isn’t about this price gouging specifically, it’s still about the power of Big Tech.

Additional Google Antitrust Thoughts

– Does this impact M&A by Big Tech? Especially when it comes to big tech snatching up smaller entertainment companies? I constantly read that Amazon should buy Viacom-CBS. Heck, just last week I wondered why Netflix doesn’t buy Sony, since they license all their shows. A source said he’s heard a lot of rumors that Netflix wants to buy Viacom-CBS. All of a sudden, mergers for vertical integration purposes look a lot dicier.

– What about entertainment mergers? That’s a good question. The ire of antitrust litigators will likely stay focused on Big Tech for the foreseeable future. If the DoJ casts their eye of Sauron around, though, Comcast and AT&T are the next in the crosshairs, given their mutual penchant for mergers, the local and national monopolies and vertical consolidation.

– Is this bad for Youtube? Potentially. One of the easy remedies for the government to insist on is that Google divest Youtube to diversify the advertising market. Given that Youtube makes almost as much money as Netflix each year in revenues, this is a reasonable request. However, the current case makes no mention of breaking up big tech, and neither did the Cicilline report.

– What about price gouging/predatory pricing in entertainment? This is much more of a stretch, but a potential spinoff branch of antitrust. In other words, under scrutiny, the DoJ could say, “Hey, if you run a video service as part of a vertically integrated firm, you can’t lose money simply to gain market share.” This is the least likely outcome of these questions, but if it were enacted it would have the largest ramifications on streaming video of any other decision.

(I had more thoughts on Quibi too that will be up at a different outlet later.)

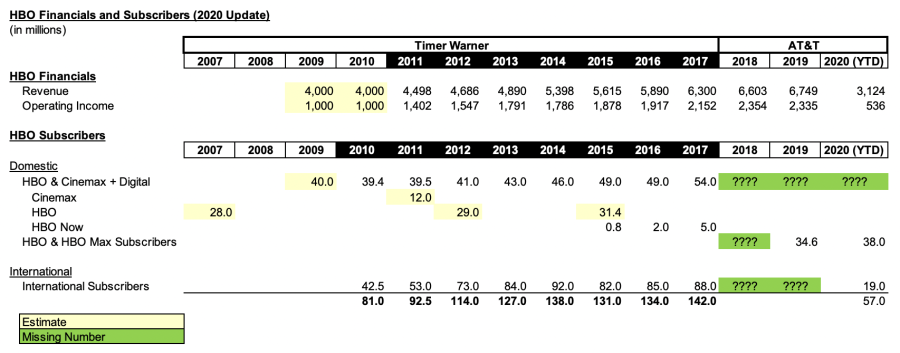

Data of the Week – What Happened to HBO’s 88 million International Subscribers?

When I spent weeks trying to figure out how much money Game of Thrones made for HBO, it required understanding HBO’s subscriber totals. Unfortunately, Warner Bros (now Warner Media) never made it easy. Before 2011 they didn’t report anything, so I had to rely on news sources. When AT&T acquired Warner Media, it stopped reporting HBO subscribers at all. Meanwhile, they combined Cinemax and HBO subscribers in the same total, even though most Cinemax subscribers were subscribed to both. To top it off, Warner never actually broke out subscribers in a table, you had to search the narrative to find the totals.

Last earnings report, AT&T decided to bring back HBO subscriber totals. So I updated my long term tracker. But AT&T decided to only report domestic/United States subscribers. Huh. Then in the latest earnings report, they added international subscribers, but claimed it was only 21 million. Double huh. So here’s my updated chart for HBO subscribers:

What happened to the 94 million at peak and 88 million as of 2017? And how high did it get in 2019 as Game of Thrones debuted?

I’ve reached out to HBO for comment, and will let you know if they reply.

Other Contenders for Most Important Story

Netflix’s Earnings Report

If you want my initial thoughts, here’s the Twitter thread:

1/ Netflix Earnings Report Thread – Q3 of 2020

Hypothesis: Netflix subscriber growth was low due to a weak content slate in the most recent quarter.

— The Entertainment Strategy Guy (@EntStrategyGuy) October 20, 2020

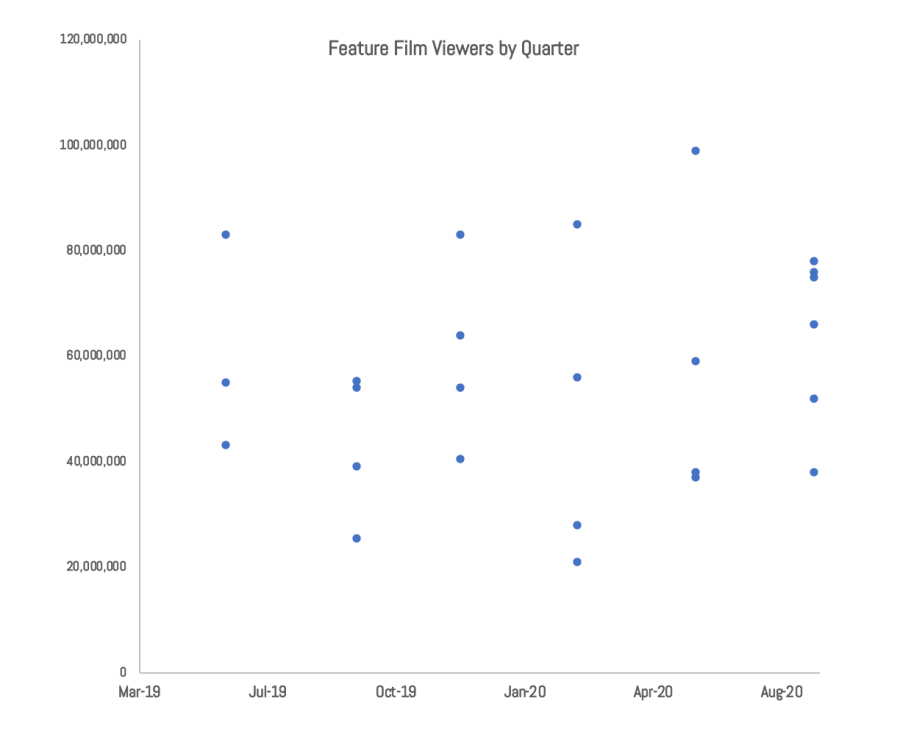

Reflecting on it, I’m surprisingly sanguine about Netflix’s earnings. I thought the content was more of a drag than it ended up being. For example, the films did pretty well with three besting the 70 million households watched by 2 minutes viewed total (55 million at 70% completion by my translation). Here’s a chart:

Caveats abound, as I like to say. First, the challenge is that the shift from 2019’s 70% completion to 2020’s 2 minutes viewed just crushes the narrative. As Netflix has said, this conversion usually means a show gains about 35% more viewers. That’s a lot. And if you took all the Netflix shows down to the 70% threshold, the numbers look less impressive.

Second, the weakness may have been in television more than anything else. Really, Netflix’s top three series are Stranger Things, The Witcher and Money Heist (La Casa de Papel), in that order. And the last of those does very poorly in the United States. Given that binge-worthy TV series drive time on Netflix, not having one of those really does hurt Netflix, and that’s why they likely missed subscriber targets in Q3.

The End of the Fast and the Furious

All things must come to an end, but even Universal’s biggest money maker of the last decade? As others said, we’ll see if Universal can hold to this promise.

A New Contender for “Next Game of Thrones”

The big question for 2022? Which series will be the “next Game of Thrones”, as I wrote about here. More than anything, every streamer is trying to mimic the success of HBO, even though it’s not clear to me audiences are clamoring for more fantasy series. (Contrary point? The Witcher did great numbers for Netflix.)

The news is that Disney+ is adapting 1988’s Willow into a TV series. This series immediately has more importance than many Netflix’ series. Mainly because Disney+ needs quarterly hits to drive subscribers and this is in “white space” that isn’t Marvel or Star Wars. (Netflix has tons of TV shows to bank on.) Plus, it could appeal to adults. Also, full disclosure: I loved Willow as a kid but haven’t rewatched on Disney+, so guess I’m doing that this weekend.

Charlie Brown Heads to Apple TV+

Well, how about that for a licensed content acquisition? All my hatred on not having a library, and then Apple grabs the Charlie Brown holiday specials, which are a tradition in many homes, exclusively for their service.

I love this move for Apple. (Caveat: price is everything, and I don’t know the terms.) For a service that needs growth, this is a great move. Honestly, I think it will drive more subscriber acquisition than Borat or Coming to America 2 for Amazon Prime Video.