Last December, I started a series whose goal was to valiantly defend the theatrical distribution model. This doesn’t come (only) from some soft spot in my heart for theaters, but from the economics of making movies. Studios can earn a lot more money by releasing their films theatrically. I’ve taken to calling this the “Booksmart Conundrum”.

Nevertheless, the question I asked last winter—“Should you release your film straight-to-streaming (Netflix) or to theaters?—is as relevant now as ever. Indeed, it’s almost quaint to imagine an article from last December is still relevant, given all that’s happened:

– Coronavirus came and closed theaters.

– Comcast (via Universal) released Trolls: World Tour straight-to-video.

– Disney put Artemis Fowl straight to Disney+, and later Hamilton.

– Netflix bought the rights to countless films and put them straight on its service too.

Does all that news invalidate my article series? Far from it. Here’s the plan. I’m going to continue my Q&A as I had it planned last December. Then, I’ll dedicate an entire article to the post-Coronavirus landscape and it’s implications.

So let’s do it.

Question: Seriously, you’re going to pretend “Covid-19/Coronavirus” never happened?

Not at all. Obviously the immediate impacts are real and I’m monitoring them in my weekly column. (Example of my latest back in June, here.)

But the core economics of releasing films in one streaming window versus multiple windows starting with theaters hasn’t really changed. They may have been tweaked given some of the new behaviors—but you know I’m skeptical on that—but Coronavirus is the “Asterisk Extraordinaire” of our time. The more confident someone is in predicting the future impact of Covid-19, the more likely they are to be wrong.

What matters for studios in the immediate term is when traditional theatrical releases restart. I still maintain that will happen before the end of the year, and likely in August. And when that happens 90% of the model will be intact. So that’s what we’ll discuss in this series.

Question: Fine, can you remind me where we were?

Sure, because I had to do it myself. To start, I finally built a straight-to-streaming financial model for films. This means that via Netflix Datecdote I can estimate how much money an individual film made for Netflix. How cool!

You can read how I built the model, why it works, and the results for The Irishman here. I built this model at the behest of the venerable Richard Rushfield for his Ankler newsletter, and showed how I can use this model very recently when I calculated the results for Extraction on Netflix too. I would add, Nina Metz at the Chicago Tribune did a great write up on my methodology too.

The most useful part of a model, though, isn’t the results but what the model tells you about how the world works. That’s the point of this series: take the model and use it to draw insights about streaming versus theatrical business models. In Part I, we focused on how much money a film makes in the various “windows” it transitions through. No matter how you cut it, theatrical distribution is a huge part of that window. Over 30% easily, but that’s actually rising as home video declines. (Also don’t neglect how home entertainment, TVOD, EST, and premium cable can add to the bottom line too.)

Another key insight is how much better the margins are better for theatrical viewing than they are for viewing at home. As a result, if you don’t release in theaters, you’re giving away potential revenue. Did I calculate this specifically for Netflix? I did, and found out, under a pretty reasonable scenario, they could have easily left $750 million dollars on the table in 2019.

Question: Three quarters of a billion dollars? Why would Netflix do that? If you were making the strongest pro-straight to streaming argument, what would it be?

The folks at Netflix aren’t crazy. They can build these models too. And the folks at Amazon tried to release their films in theaters. The most generous explanation I can give would go like this:

When a film goes to theaters first, it risks being viewed as unpopular if it flops. That would destroy the value on the streaming platform. Moreover, by going straight-to-streaming, Netflix and others have the added value of exclusivity on the platform, driving new subscribers. This is really the point of putting films on streaming anyways, to acquire and retain subscribers.

That’s really two explanations in one. First, failure at the box office destroys value and second that exclusivity raises value.

Q: Is this a strawman, or do you have someone making this argument explicitly?

This is the argument Scott Stuber—Netflix head of film— made to Variety at their conference. His quote:

Essentially, he’s more afraid that film will bomb at the box office than it won’t perform on his service.

Essentially, he’s more afraid that film will bomb at the box office than it won’t perform on his service.

Well, I have a two word answer for him:

Late Night.

Q: What does Late Night have to do with it?

Late Night is about the absolute biggest flop you can have for a feature film, narratively at least. It was a huge Sundance Acquisition that Amazon put a bunch of money into marketing. And for all their efforts, they were rewarded with…

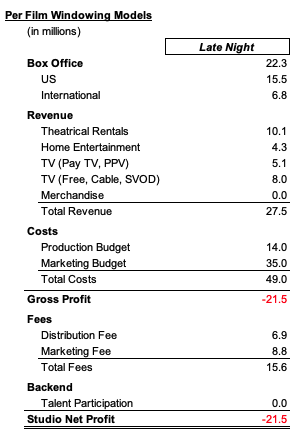

That’s right, a $21.5 million loss, if you use traditional accounting.

Q: But Late Night didn’t go to cable, it went straight-to-streaming. What about that?

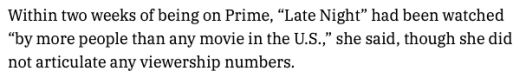

When it came out on Prime, and according to Jen Salke, the head of Amazon Studios at another conference (seriously, how many conferences were there before coronavirus?), Late Night was a huge hit for Amazon Studios.

Q: You lost me. So Late Night was a hit on streaming, shouldn’t it have made money?

Q: You lost me. So Late Night was a hit on streaming, shouldn’t it have made money?

Still no. Basically, Stuber and Salke are getting the causation backwards. They think if a film does poorly at the box office, it won’t perform on streaming, which is where they make their money. For Salke, this is justification to skip theaters, but I’d actually argue its precisely the opposite: it’s an argument to keep releasing films in theaters because no matter how they do, customers will still watch on streaming.

Essentially, the first worry of Netflix/Amazon executives isn’t true.

(Also, I’d have done a “theaters plus streaming” version of my model for Late Night, but Amazon has never released numbers for us. But it doesn’t matter because box office imparts the value of the film.)

Q: Then box office doesn’t matter at all for future viewership?

I didn’t say that, in fact I said the opposite. My model—and this is based on tons of experience—is that viewership and hence “value” is a function of theatrical box office. Which is a function of the unquantifiable “popularity”.

Indeed, if Late Night had been a huge hit at the box office, it likely would have had even larger viewership on Prime Video. (And frankly Salke knows this.)

Q: What do you mean “function”?

Well, good old fashioned algebraic equation. Which is what most “regression analysis” is. Consider this function:

Y = 2x.

Y is a “function” of x, in that if you know x, you know Y is two times larger.

This is how most “algorithms” work, even though we imagine them to be infinitely complicated, unknowable mathematic equations. They can be huge and super complicated, but at the end of the day they’re about relationships.

My theatrical model treats feature film financials as a function of box office. Essentially, everything is derived from that first number in the process, as a decreasing function in value.

Q: Does that work out in real life?

Absolutely. Box office results are correlated with future revenue streams. And not just a little bit correlated, but highly correlated. This means that usually by a Friday afternoon, a movie studio knows if it will make money on a theatrical release or not.

Q: Are streaming views correlated with box office too?

Yep!

This is how studios sell their content to Netflix and Amazon and how the streamers in turn determine the prices for second windows. They use box office as proxy for popularity on streaming and 95% of the time it’s pretty darn accurate.

The key change is the “margins” which I described in the first article. Since you make so much less money on streaming, the value of the digital window is much, much smaller. Hence, a movie that makes say $100 million at the box office is only worth $1-10 million in streaming.

Literal orders of magnitude smaller.

Q: Does that mean less people watch so they get less value?

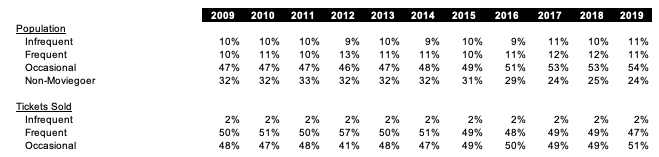

Actually, it’s the opposite situation. Way, way more people watch movies at home, and they pay way less to access either cable or streaming, so the value per film is that much smaller for the studios. The vast majority of feature film viewership occurs at the home anyways. As others have noted, the average American buys about four movie tickets per year, which is actually heavily skewed as most Americans buy less than 2, but a few theater attendees (myself included) buy a lot.

This table from the MPAA shows how much frequent moviegoers account for all tickets sold based on their annual survey results.

In other words, it’s easy to get 20 million people to watch a film on Netflix; it’s really hard to get 20 million people to watch a film in the theaters.

Q: This explains why Jen Salke had lots and lots of people watch Late Night even though it bombed at the box office?

Precisely.

That’s essentially the game Stuber and Salke are playing with their numbers for straight-to-streaming releases. A really valuable audience is 20 million people willing to leave their homes to go to theaters. There are a lot of films that can get 20 million people to tune in at their homes for it. But as a result, since there are so many films like that, they aren’t nearly as valuable in retaining and acquiring subscribers.

My model accounts for this. That’s why as a film gets more popular, the value it adds in retained and acquired subscribers goes up directly.

Q: What about the value of “exclusivity” on the platform?

The idea is that if a film skips theaters, it becomes more valuable to the streamer doesn’t make sense. That perceived value is why streamers skip theaters.

Again, this is a red herring. The value comes from “popular’ films meaning a film lots and lots of people want to see. An unpopular film that goes straight to your platform is still unpopular. Though folks may watch it anyways. But they won’t “value” it, which means they won’t stay with your service because to it. And a popular film will get some people to your platform, but you would have made more money in theaters, and then going to a streamer.

Q: If people see a film in theaters, maybe then they won’t see it later when it’s on Netflix or HBO or what not?

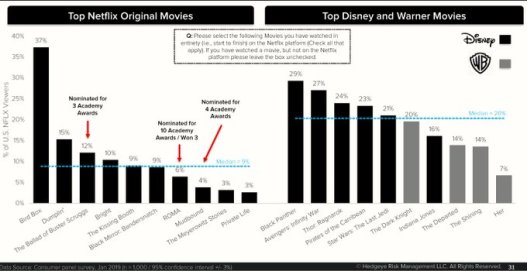

Again, box office is a great proxy for popularity. And films that were popular in theaters tend to be very, very popular on streaming too. Now it’s hard to get a lot of good data on this since Netflix never releases licensed streaming numbers. But when some third party analyzes Netflix, they tend to see this effect.

For example, here’s Hedgeye’s survey result. Look at how as of last January of 2019, Disney films were clearly more popular than Netflix originals.

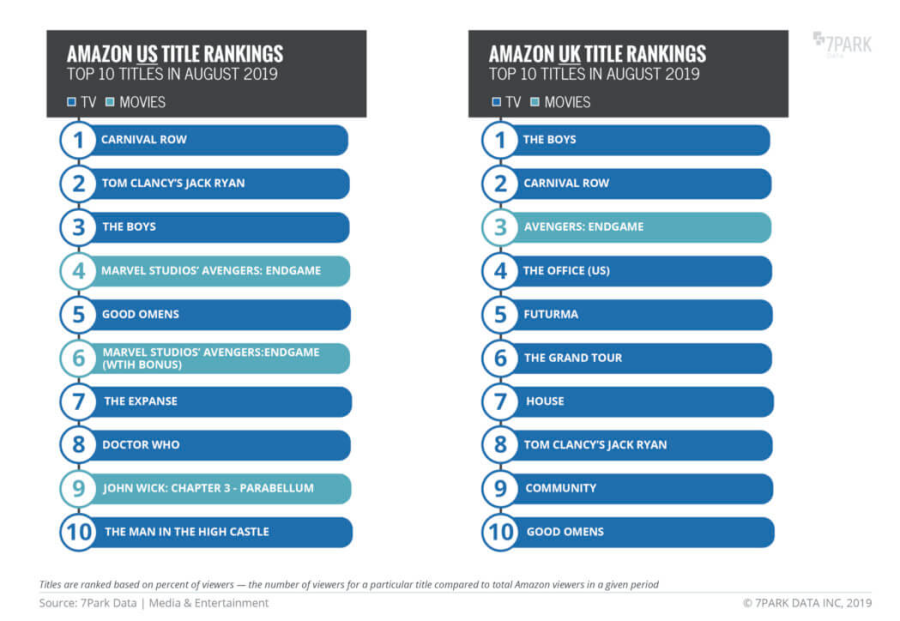

To pick on Amazon, here’s a third party looking at the most popular films on Prime Video:

The crazy thing is that Avengers: Endgame wasn’t even available on Prime video! This means more people bought Avengers than watched free movies on Prime. Again that’s value!!!

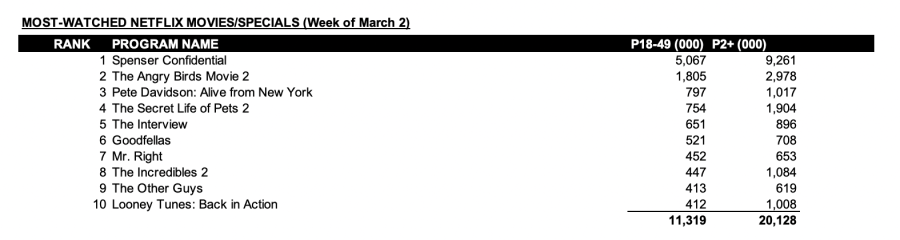

Finally, Netflix started releasing global top ten lists since I started this series. What are the results from that? Well again, licensed movies tend to do very well. This isn’t their data, but you can see from Nielsen data back in March that licensed films tend to easily compete with Netflix original films. Indeed, they’re often half of the film list (and tend to importantly stay on the list for weeks after their release.)

Q: Anything else?

Q: Anything else?

Lots, but we’ll save it for a future article.