As the self-appointed judge of what is “most important” in entertainment each week, I often remind myself that “story” doesn’t mean “event”. That’s why I’m so excited about this week’s story. If a trend is happening slowly, sometimes it flies under the radar, and we miss it entirely, which doesn’t mean the trends aren’t important; they are. And today we have a perfect example.

(Sign up for my newsletter to get my column and streaming ratings report delivered to your inbox.)

Most Important Story of the Week – Is Netflix Finally Feeling the Covid-Induced Production Slowdown?

If I have one gripe about the coverage of the streaming wars—strike that. I have lots of gripes. Who am I kidding?—anyways, one of my gripes is that sometimes the world’s biggest streamer gets treatment that other companies just don’t. It’s as if the rules that apply to traditional entertainment studios just don’t apply to Netflix because they’re a “tech giant” “disrupting” the “ecosystem”.

Which they are! But that doesn’t mean the laws of physics don’t apply to them.

This played out last spring into the fall. When Covid swept the world, one of the consequences was that entertainment supply—the making of shows and films, the “production”—ground to a halt. If folks couldn’t gather without spreading the virus, they couldn’t gather to produce content.

As a result, the traditional broadcast networks had to delay everything to winter premieres. Meanwhile, a few streamers like Peacock and HBO Max had to delay their splashy new originals. Disney+ too. In short, everyone was hurting.

Except for Netflix.

In one of their earnings reports—I believe after Q2—Netflix said they had mostly “returned to normal” production. Since they kept releasing new content through the fall, folks assumed they had essentially beat the pandemic production pause. Unlike traditional studios, who had to stop production and then didn’t air new content, Netflix was fine. Another triumph for Reed Hastings and team!

At the time, I pointed out that this was temporary. Netflix couldn’t defy the laws of production physics. If they stopped all production like everyone else, that would show up in the numbers. And indeed, it finally has. Let’s explain what is going on, why it’s happening, and what a content slowdown means for the streaming wars.

The Situation: Netflix Is Releasing Less Content Historically

The data for this comes from What’s-On-Netflix, a website I use when analyzing streaming ratings because of their robust data sets. Founder Kasey Moore put out these tweets:

Netflix first of the month additions for April for the past few years:

2021: 40

2020: 83

2019: 62

2018: 81— Kasey Moore (@kasey__moore) April 1, 2021

And here is year to date and “originals”:

Netflix Originals:

'21: 159

'20: 180

'19: 143It'd be very fair to say the content drought is here 😉

— Kasey Moore (@kasey__moore) April 1, 2021

Without getting too in the weeds today, and having reviewed his data, this story checks out. (Moore is a friend of the site and we’ve talked about this for months. I hope to write on it more in future streaming ratings articles.) Another friend of the website, sell-side analyst Andrew Freedman drew the same conclusion last year:

In proper context, this is the most accurate thing to say: Netflix is still releasing more content than they were as of 3 or 4 years ago. But compared to recent history (2019 and 2020), they have definitely slowed down. And this is impacting both original shows (meaning produced for Netflix directly) and licensed titles. Let’s explore the reasons for both.

Original Productions: Netflix Has Very Long Production Lead Times

One thing I realized during the pandemic was that I had underestimated one key facet of Netflix’s production. See, I used this rule of thumb for producing a TV show:

3/ So here it is:

X Weeks – Writing

6 Weeks – Pre-production

1-2 Weeks – Shooting (5 biz days for half hour; 10 for dramas. Single cam)

4-6 Weeks – Editing

4 Weeks – Post Production— The Entertainment Strategy Guy (@EntStrategyGuy) June 5, 2020

(This thread describes a lot of the production timelines I’ll discuss below, though, even at the time, I didn’t realize how much longer Netflix’s post-production timeline was compared to U.S.-only streamers.)

These lengths of times are my “rule of thumb” for a TV show. They aren’t the same in every case, but most of the time, yeah, they work out. To start a show, it requires about six weeks to get everything ready. And if you’re recording an hour of TV, most of the time that takes 10 shoot days, with a weekend in between. So two weeks.

But two things are different from Netflix compared to broadcast TV. First, the binge release. In TV, it takes six weeks to set up in pre-production, then two weeks to shoot an episode, then four weeks to edit it, then some time for post-production. Then a broadcaster can air the episode.

Not so with the binge. If you’re releasing ten episodes at the same time, the earliest your last episode can go up is four weeks from when the last episode finishes shooting. So that means that Netflix will take 10-20 weeks longer to finish a season. Since all episodes go up simultaneously, the timeline for releasing a season is essentially the same as the timeline for the last episode.

Then you have post-production. In days of yore, life was simpler and you’d film and edit a show, and that was the version you put on TV. In one country. In its language. Eventually, it would go overseas.

Nowadays, streamers often need multiple versions, for different visual definitions (standard, high and ultra high definition). For Netflix, this goes a step function further in that they need different languages and dubs for nearly every single territory. Meaning, their post-production timeline is vastly longer than my four weeks accounting above.

Which is something I had underestimated even as of last June. I didn’t realize that in some cases, Netflix takes 6-9 months after production concludes to finish editing, dubbing and post-producing a show. Since they have such long time frames, that was how they were able to keep releasing content into the fall. Most of the shows like The Queen’s Gambit or Cobra Kai or Bridgerton were likely finished shooting before Covid-19 shut everything down. (Or mostly shot.) Stranger Things, which had just started production when Covid hit, likely won’t air until August. Since it was likely arriving in December of last year, that’s a 9 month delay. The Covid production pause in action.

Add these two factors up? And it takes quite a long time from the start of production to get a show streaming on Netflix. Covid-19 delayed Netflix as long as everyone else, it just took much longer to show up in the calendar.

Licensed content is similarly impact. For all the focus on originals, Netflix licenses quite a few TV shows that drive lots of viewing. If a bunch of broadcast dramas are delayed because of the pandemic—shows like The Blacklist, Grey’s Anatomy or The CW series—their arrival in a second window on Netflix will be delayed as well. Same for films: if all theatrical films are delayed, then they’ll be delayed in showing up on Netflix too.

The Ramifications

How bad is this long term? I could argue both sides.

The “this isn’t that big of a deal case” is pretty simple: even with this content slowdown, Netflix has such a head start that they still dominate the Nielsen weekly top ten charts. See:

While Netflix hasn’t released as much content, they still have new shows and films nearly every week. This quarter saw Ginny & Georgia, Firefly Lane and Yes Day, for example. Still tons of new content! (They’ve still added 159 new originals this year!) And seemingly some of their competitors are stuck in the same boat: Amazon’s Lord of the Rings series was delayed by Covid too, and Hulu hasn’t released a buzzy original in who knows how long.

While Netflix hasn’t released as much content, they still have new shows and films nearly every week. This quarter saw Ginny & Georgia, Firefly Lane and Yes Day, for example. Still tons of new content! (They’ve still added 159 new originals this year!) And seemingly some of their competitors are stuck in the same boat: Amazon’s Lord of the Rings series was delayed by Covid too, and Hulu hasn’t released a buzzy original in who knows how long.

But this isn’t all sunshine and roses. Right when Netflix’s content is slowing down, two of their four biggest streaming competitors are going all out for customers. Disney has launched two shows that—depending on how you count—are as popular as anything on Netflix. (And The Falcon and the Winter Soldier started strong too.)

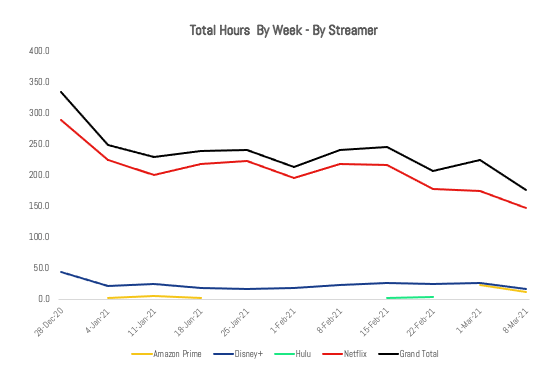

Meanwhile, nothing in the Q1 arsenal compares to the Q4 deluge Netflix dropped. In hindsight, the fantastic Q4 shows like The Crown, Bridgerton and The Queen’s Gambit really did drive tons of usage. Comparing this year to last year, this last quarter pales to the end of Q1/beginning of Q2 of last year, which saw an incredible stretch of Love is Blind into Tiger King into Ozark into Money Heist, bookended by Spenser Confidential and Extraction. As such, total streaming volume is down year over year by the four streamers Nielsen tracks:

(This is from my latest streaming ratings report.)

And the competition is only ramping up. Discovery+ debuted in January, and Paramount+ rebranded with a big marketing campaign in March. Netflix having a content slowdown provides competitors with an opportunity.

Listen, the streaming wars are a slog. A multi-year war that may never end. This isn’t the Franco-Prussian War or the Gulf War, both of which ended in the length of months, not years. This is much more like World War I, where each side is entrenched and fighting for inches of ground day-after-day.

And that’s the downside for the content slowdown. The worry, if I’m Netflix, isn’t that all my subscribers leave overnight. No one is saying that will happen. (Again, no one.) But right now, Netflix has a streaming leadership in the key metrics like churn, retention and usage of its platform. If the decline in content encourages folks to check out HBO Max or Disney+ or Paramount+ or Discovery+, those numbers could weaken. Long term, that could hurt Netflix. Meaning they may still be the leader in streaming, but their lead could shrink.

Conclusion: Netflix is in the Hit-Making Business

The one inescapable conclusion, though, is that for all Netflix has innovated, at the end of the day, they’re in the hit-making business. The more hits they make, the better their service will do overall.

We’ve seen that in the data, and tentatively, I think we’ll see that in their subscriber numbers over time. Quarters with great content (Q1 and Q4 of 2020, Q4 of 2019) will see better growth. Weaker quarters may be flat. (Though this will be a loose correlation at best, with quite a few confounding variables.) So Netflix can run from the old-fashioned idea that you’ve got to make hits to win, but they may not outrun it.

M&A Updates – Televisa and Univision Join Forces

In an upcoming article, I’m going to write about “M&A” games. That’s where, instead of working on strategy, which is hard, you focus on M&A, buying or merging with competitors to make strategy easy. (Remember, M&A isn’t strategy!)

If you were playing M&A games, though, it’s hard to find a better move than this merger. Univision is a powerhouse in the American hispanic television market, but as a broadcaster, they’re fairly constrained in merging with any traditional entertainment players, since that would violate broadcast station ownership rules. To bulk up, then, they merged with a powerhouse of Mexican content production and distribution, Televisa. The hope is that, together, they can develop a streaming alternative to Netflix with a focus on Latin American content.

We’ll see if it works. Again, mergers aren’t strategy, but as far as this one goes, it was a smart move. The key is focus: concentrate on a Spanish language-only product that understands hispanic speakers at a deeper level than global streamers trying to do it all. Can they pull it off?

(In the future, I’d love to go deeper on the Spanish language streaming wars. That’s a fun battlefield.)

Other Contenders for Most Important Story

Amazon Passes 200 Million Prime Subscribers

If you follow the news, you saw this headline. Just remember, those 200 million are not the same thing as “Prime Video users”. Nor are Prime Video users the same thing as “folks who would pay for Prime Video”. But tons of charts will now use this number to make it seem like Prime Video is as big as Netflix globally. Sigh.

(Want a better look? Here’s my estimates back in November, which I’ll update in May. I promise.)

Sports Ratings Are Back?

That’s the too soon conclusion one could draw after hearing that both The Masters and the NCAA men’s basketball tournament saw increases in viewership compared to their past years. Longer term, sports will continue to see a decline in linear viewership; that’s just the future. In the interim? Live sports will provide the best ratings and broadcasters have to like these numbers.

Disneyland Opened Up Reservations; They Were Swamped

Overall, it looks like demand to return to Disneyland will be high when the park reopens in April. Though Disneyland hasn’t sold out of all reservations for their first two months, that seems to be more of a function of limiting the reservation system to ensure folks can buy tickets. Let’s wait for more data, but the sooner Disneyland sells out, the higher the likelihood that the Covid recovery is on track.

Lots of News with No News – Pacific Theaters (Cinerama Dome & ArcLight) Are Shutting Down

This week, I joined my fellow cinephiles in the rending of garments and wailing of voices and gnashing of teeth over the truly terrible news that the Pacific theater chain—who owns the ArcLight theaters and Pacific theaters—would be shutting down for good. (Here were my initial thoughts.)

I’ve softened since the news for two reasons, though I am still very disappointed they haven’t reopened.

First, I’m not ready to translate this news into the larger doom narrative for theaters. Frankly, the reasons that AMC and Cinemark have been able to reopen are different from the reasons why the ArcLight can’t. AMC happens to be well-capitalized from their convenient Wall Street Bets-fueled stock sales and some debt restructuring.

Thus, landlords can use the threat of AMC taking over abandoned ArcLight locations as pressure to force ArcLight to pay back rent or to pay higher rent right now. Long term, if all theatrical filmgoing disappears, then landlords with giant multiplexes are toast. As long as AMC and Cinemark survive, especially in high wealth locations, though, landlords will be fine. Smaller players, like ArcLight, are the losers in this situation.

Second, note that Pacific Theaters has not actually filed for bankruptcy. If you’re ending your operations, that’s what you do. File for bankruptcy, and wind down legally. So why not? Well, perhaps this announcement is part of a long term pressure campaign to get a government bailout or renegotiate with landlords.

Or as I hit publish, we’ll see news they have filed for bankruptcy. All to say this saga will still unfold. This isn’t “no news” but probably isn’t as bad as it seems. (I hope.)